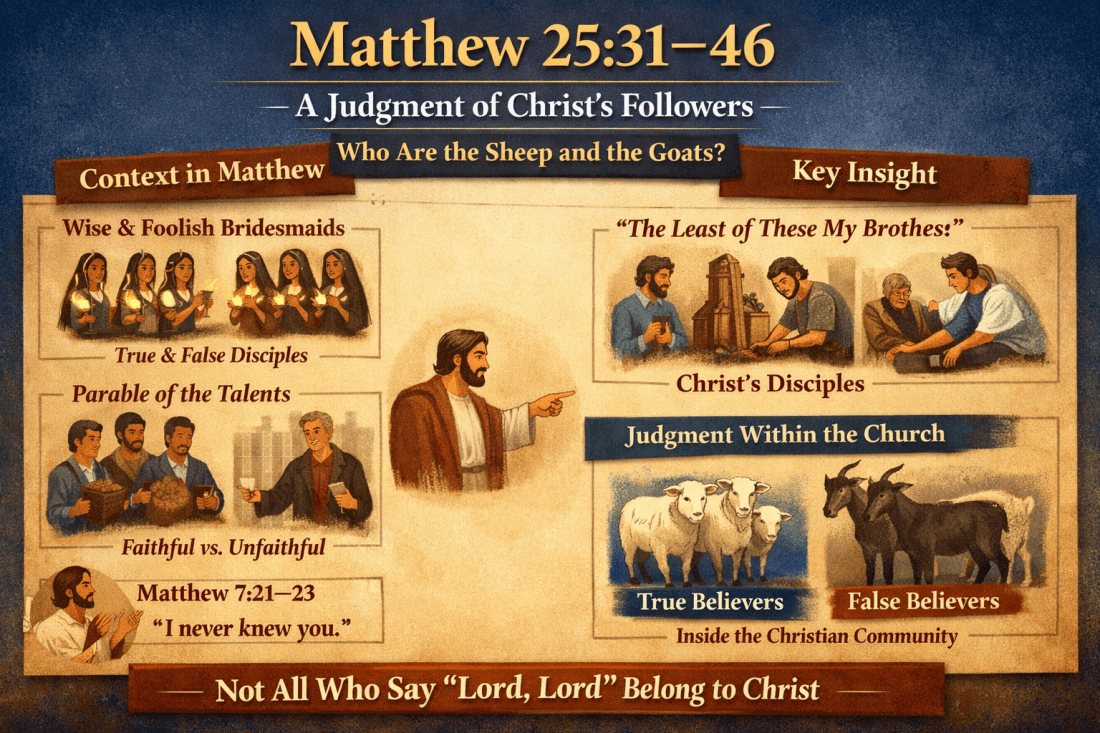

The famous “sheep and goats” judgment in Matthew 25 is often assumed to describe the final judgment of all people. But when read alongside the surrounding parables and Jesus’s teaching about false disciples, a different picture emerges: a warning that not everyone within the visible community of Christ truly belongs to him.

Consider the text…

31 “When the Son of Man comes in his glory and all the angels with him, then he will sit on the throne of his glory. 32 All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats, 33 and he will put the sheep at his right hand and the goats at the left. 34 Then the king will say to those at his right hand, ‘Come, you who are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world, 35 for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, 36 I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me.’ 37 Then the righteous will answer him, ‘Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry and gave you food or thirsty and gave you something to drink? 38 And when was it that we saw you a stranger and welcomed you or naked and gave you clothing? 39 And when was it that we saw you sick or in prison and visited you?’ 40 And the king will answer them, ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did it to me.’ 41 Then he will say to those at his left hand, ‘You who are accursed, depart from me into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels, 42 for I was hungry and you gave me no food, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink, 43 I was a stranger and you did not welcome me, naked and you did not give me clothing, sick and in prison and you did not visit me.’ 44 Then they also will answer, ‘Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry or thirsty or a stranger or naked or sick or in prison and did not take care of you?’ 45 Then he will answer them, ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did not do it to one of the least of these, you did not do it to me.’ 46 And these will go away into eternal punishment but the righteous into eternal life.”

This, and all following scripture references are from the NRSV

This passage is often seen as Christ’s judgement of all humanity at the end of days. But, I disagree. To me this is a judgement of those who claim to be followers of Christ.

First, read the two parables that come before this judgement passage: The Parable of the Ten Bridesmaids (Matt. 25:1-13) and The Parable of the Talents (Matt 25:14-30). Not going into the details about what those parables mean, notice who the characters are in the parables. The three servants who are given the talents all serve the same master, and the ten maids are all waiting for the same bridegroom. These parables are not about unbelieving outsiders vs. believing insiders. These parables are about true disciples vs. false disciples within the group.

Next, read what Jesus says in Matthew 7…

15 “Beware of false prophets, who come to you in sheep’s clothing but inwardly are ravenous wolves. 16 You will know them by their fruits. Are grapes gathered from thorns or figs from thistles? 17 In the same way, every good tree bears good fruit, but the bad tree bears bad fruit. 18 A good tree cannot bear bad fruit, nor can a bad tree bear good fruit. 19 Every tree that does not bear good fruit will be cut down and thrown into the fire. 20 Thus you will know them by their fruits.

Matthew 7:15-23

21 “Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but only the one who does the will of my Father in heaven. 22 On that day many will say to me, ‘Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in your name, and cast out demons in your name, and do many mighty works in your name?’ 23 Then I will declare to them, ‘I never knew you; go away from me, you who behave lawlessly.’

Here we see something similar to Matthew 25. There are people claiming to be prophets of God, who call Jesus “Lord,” just as the goats do in Matthew 25. They are not rejected because they are outside of the Jesus group, but because they are false disciples within the Jesus group.

Next, consider Matthew 10. Here, Jesus sends out the twelve, his closest disciples…

16 “I am sending you out like sheep into the midst of wolves, so be wise as serpents and innocent as doves. 17 Beware of them, for they will hand you over to councils and flog you in their synagogues, 18 and you will be dragged before governors and kings because of me, as a testimony to them and the gentiles. 19 When they hand you over, do not worry about how you are to speak or what you are to say, for what you are to say will be given to you at that time, 20 for it is not you who speak, but the Spirit of your Father speaking through you. 21 Sibling will betray sibling to death and a father his child, and children will rise against parents and have them put to death, 22 and you will be hated by all because of my name. But the one who endures to the end will be saved. 23 When they persecute you in this town, flee to the next, for truly I tell you, you will not have finished going through all the towns of Israel before the Son of Man comes.

24 “A disciple is not above the teacher nor a slave above the master; 25 it is enough for the disciple to be like the teacher and the slave like the master. If they have called the master of the house Beelzebul, how much more will they malign those of his household!

26 “So have no fear of them, for nothing is covered up that will not be uncovered and nothing secret that will not become known. 27 What I say to you in the dark, tell in the light, and what you hear whispered, proclaim from the housetops. 28 Do not fear those who kill the body but cannot kill the soul; rather, fear the one who can destroy both soul and body in hell [Gehenna]. 29 Are not two sparrows sold for a penny? Yet not one of them will fall to the ground apart from your Father. 30 And even the hairs of your head are all counted. 31 So do not be afraid; you are of more value than many sparrows.

32 “Everyone, therefore, who acknowledges me before others, I also will acknowledge before my Father in heaven, 33 but whoever denies me before others, I also will deny before my Father in heaven.

This passage contains one of the five times the word Gehenna is used in Mathew, and it’s directed at Jesus’s closest twelve disciples.

Paul also explains in Romans 9 that within the covenant group of Israel there is the true Israel and the false Israel…

6 It is not as though the word of God has failed. For not all those descended from Israel are Israelites, 7 and not all of Abraham’s children are his descendants, but “it is through Isaac that descendants shall be named for you.” 8 This means that it is not the children of the flesh who are the children of God, but the children of the promise are counted as descendants.

When the judgment scene of Matthew 25:31–46 is considered within the broader literary context of the Gospel of Matthew, it appears less likely that the passage is intended primarily as a description of the judgment of all humanity in general. Rather, the surrounding parables and Jesus’s earlier warnings about false disciples suggest that Matthew is addressing a persistent concern within the covenant community itself: the distinction between those who genuinely belong to Christ and those whose allegiance is only outward.