Category: Early Christianity

Chart of Events/Figures in Both Josephus and Acts

| Event/Figure | Description in Acts | Description in Josephus | Approximate Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Herod Agrippa I’s Death | Acts 12:20–23 describes Herod being struck down by God and eaten by worms after accepting divine worship. | Antiquities 19.8.2 describes Agrippa’s death at Caesarea, struck by illness during a festival, possibly due to poisoning or divine punishment. | 44 AD |

| Gamaliel the Pharisee | Acts 5:34–39 mentions Gamaliel, a respected Pharisee, advising the Sanhedrin to leave the apostles alone. | Antiquities 20.9.4 and other references describe Gamaliel as a prominent Pharisee and teacher, respected in Jewish society. | ~30–50 AD |

| Theudas the Insurrectionist | Acts 5:36 references Theudas, a false prophet whose rebellion failed. | Antiquities 20.5.1 describes Theudas leading a revolt, later executed by Roman authorities. | ~44–46 AD |

| Judas the Galilean | Acts 5:37 mentions Judas leading a revolt during the census, later killed. | Antiquities 18.1.1 and Jewish War 2.8.1 describe Judas the Galilean’s revolt against the Roman census, founding the Zealot movement. | ~6 AD |

| Famine under Claudius | Acts 11:27–30 describes a great famine in Judea, prompting relief from Antioch Christians. | Antiquities 20.2.5 and 20.5.2 mention a severe famine in Judea under Claudius, alleviated by Queen Helena of Adiabene. | ~46–48 AD |

| Herod Agrippa II and Bernice | Acts 25:13–26:32 describe Paul’s trial before Agrippa II and Bernice in Caesarea. | Antiquities 20.7.2–3 and Jewish War 2.15.1 mention Agrippa II and his sister Bernice, their roles, and interactions with Roman governors. | ~59–62 AD |

| Felix, Roman Governor | Acts 23:24–24:27 describes Paul’s imprisonment and trial under Felix. | Antiquities 20.7.1–2 and Jewish War 2.13.2 describe Felix’s governorship and harsh rule in Judea. | ~52–60 AD |

| Festus, Roman Governor | Acts 24:27–25:12 mentions Festus succeeding Felix and handling Paul’s case. | Antiquities 20.8.9–10 describes Festus’s appointment and efforts to suppress unrest. | ~60–62 AD |

| Ananias, High Priest | Acts 23:2–5 describes Ananias ordering Paul struck during his trial. | Antiquities 20.5.2 and 20.9.2 mention Ananias as high priest, later assassinated for corruption. | ~47–59 AD |

Explanations and Notes

- Herod Agrippa I’s Death (44 AD):

- Acts: Portrays Agrippa’s death as divine judgment for accepting worship as a god, with an angel striking him, leading to death by worms (Acts 12:20–23).

- Josephus: Describes Agrippa falling ill at a festival in Caesarea, possibly due to poisoning or a medical condition, dying after five days (Antiquities 19.8.2). Both accounts align on the sudden and dramatic nature of his death.

- Historical Context: Agrippa I, king of Judea, was a key figure under Emperor Claudius. His death created a power vacuum, leading to direct Roman rule.

- Gamaliel the Pharisee (~30–50 AD):

- Acts: Gamaliel, a respected Sanhedrin member, advises caution regarding the apostles, citing past failed movements (Acts 5:34–39).

- Josephus: Mentions Gamaliel as a leading Pharisee and teacher, influential in Jewish legal circles (Antiquities 20.9.4). He is likely the same figure, possibly Paul’s teacher (Acts 22:3).

- Note: The timing of Gamaliel’s speech in Acts aligns with early Christian persecution (~30–35 AD), though Josephus’s references are less specific.

- Theudas the Insurrectionist (~44–46 AD):

- Acts: Gamaliel references Theudas’s failed revolt as an example of movements that collapse (Acts 5:36).

- Josephus: Describes Theudas leading followers to the Jordan River, claiming prophetic powers, but killed by Roman forces (Antiquities 20.5.1).

- Issue: Acts places Theudas before Judas the Galilean (6 AD), creating a chronological discrepancy, as Josephus dates Theudas to ~44–46 AD. This may reflect a narrative anachronism in Acts or a different Theudas.

- Judas the Galilean (~6 AD):

- Acts: Mentions Judas’s revolt during the census, which failed (Acts 5:37).

- Josephus: Describes Judas leading a tax revolt against Rome during Quirinius’s census, founding the Zealot movement (Antiquities 18.1.1; Jewish War 2.8.1).

- Context: The census (6 AD) sparked widespread unrest, and Judas’s movement influenced later Jewish rebellions.

- Famine under Claudius (~46–48 AD):

- Acts: Describes a famine predicted by Agabus, leading to Christian relief efforts (Acts 11:27–30).

- Josephus: Notes a severe famine in Judea, with Queen Helena of Adiabene providing aid (Antiquities 20.2.5).

- Context: The famine under Emperor Claudius aligns with historical records of grain shortages in the eastern Mediterranean.

- Herod Agrippa II and Bernice (~59–62 AD):

- Acts: Agrippa II and Bernice hear Paul’s defense in Caesarea, with Agrippa noting Paul could have been freed if not for his appeal to Caesar (Acts 25:13–26:32).

- Josephus: Details Agrippa II’s role as a Roman client king and Bernice’s controversial presence (Antiquities 20.7.2–3).

- Context: Agrippa II ruled parts of Judea and advised Roman governors, while Bernice was a prominent figure, later linked to Titus.

- Felix, Roman Governor (~52–60 AD):

- Acts: Felix oversees Paul’s trial, keeps him imprisoned, and hopes for a bribe (Acts 23:24–24:27).

- Josephus: Describes Felix’s governorship, marked by harsh measures against Jewish rebels (Antiquities 20.7.1–2).

- Context: Felix’s rule was turbulent, contributing to rising tensions in Judea.

- Festus, Roman Governor (~60–62 AD):

- Acts: Festus succeeds Felix, hears Paul’s case, and sends him to Rome (Acts 24:27–25:12).

- Josephus: Notes Festus’s efforts to manage Jewish-Roman conflicts (Antiquities 20.8.9–10).

- Context: Festus’s brief governorship preceded the First Jewish-Roman War.

- Ananias, High Priest (~47–59 AD):

- Acts: Ananias orders Paul struck during his trial, prompting Paul’s rebuke (Acts 23:2–5).

- Josephus: Describes Ananias’s corrupt tenure and eventual assassination by Jewish rebels (Antiquities 20.9.2).

- Context: Ananias was a polarizing figure, aligned with Roman interests.

Comparison: The Egyptian in Acts and Josephus

| Event/Figure | Description in Acts | Description in Josephus | Approximate Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Egyptian (False Prophet/Rebel) | Acts 21:38 mentions a Roman tribune asking Paul if he is “the Egyptian” who led a revolt and took 4,000 “assassins” (Sicarii) into the wilderness. | Jewish War 2.13.5 and Antiquities 20.8.6 describe the Egyptian as a false prophet who led a large following (30,000, per Josephus) to the Mount of Olives, promising to overthrow Roman rule, but was defeated by Felix’s forces. | ~52–58 AD |

Detailed Comparison

- The Egyptian in Acts:

- In Acts 21:38, during Paul’s arrest in Jerusalem, a Roman tribune (Claudius Lysias) mistakes Paul for “the Egyptian,” asking, “Are you not the Egyptian, then, who recently stirred up a revolt and led the four thousand men of the Assassins (Sicarii) out into the wilderness?” (ESV). This implies the Egyptian was a known figure associated with a recent uprising.

- The “Sicarii” were a radical Jewish group known for assassinations, often targeting Roman collaborators. Acts suggests the Egyptian led a significant number of them, though the scale (4,000) is smaller than Josephus’s account.

- The Egyptian in Josephus:

- In Jewish War 2.13.5, Josephus describes the Egyptian as a false prophet who gathered a large following—around 30,000 people—and led them to the Mount of Olives, claiming he would cause the walls of Jerusalem to fall, signaling the overthrow of Roman rule. Roman governor Felix attacked, dispersing the group, and the Egyptian escaped.

- In Antiquities 20.8.6, Josephus provides a similar account, noting the Egyptian’s messianic claims and Felix’s decisive response. He emphasizes the Roman crackdown on such movements, which were common during this period of unrest.

- The discrepancy in numbers (4,000 in Acts vs. 30,000 in Josephus) may reflect exaggeration by Josephus, a common trait in ancient historiography, or a difference in sources.

- Historical Context and Overlap:

- Date: Both accounts place the Egyptian’s revolt during Felix’s governorship (52–60 AD), likely around 55–58 AD, aligning with the turbulent period leading up to the First Jewish-Roman War (66–73 AD).

- Nature of the Figure: Both sources depict the Egyptian as a messianic or prophetic figure leading a rebellious movement against Roman authority, fitting the pattern of 1st-century Jewish uprisings. Acts’ reference to the Sicarii connects him to violent resistance, while Josephus emphasizes his role as a false prophet with a large, albeit short-lived, following.

- Location: Acts mentions the wilderness, while Josephus specifies the Mount of Olives as the staging ground for the Egyptian’s demonstration, which overlooks Jerusalem—a symbolically significant location for messianic expectations.

- Differences and Interpretation:

- Acts provides a brief, secondhand reference, using the Egyptian as a point of mistaken identity to highlight the Roman perception of Paul as a potential revolutionary. Josephus, writing as a historian, gives a more detailed narrative, focusing on the event itself and its political implications.

- The numerical difference (4,000 vs. 30,000) could stem from Acts relying on a Roman report (via the tribune) with a more conservative estimate, while Josephus, writing later, might inflate numbers to emphasize the scale of unrest under Roman rule.

- Neither source names the Egyptian, and his fate remains unclear—Josephus notes he fled, while Acts offers no further details.

AI’s Hypothetical Religion

I asked AI this question: If someone were to combine second temple messianic Judaism with the mystery religions and Greek mythology in order to create their own religion, what do you think that made up religion would look like?

AI’s response…

Creating a syncretic religion by blending Second Temple Messianic Judaism, mystery religions (like those of Mithras, Isis, or Dionysus), and Greek mythology would result in a fascinating and complex belief system. Let’s imagine what this might look like by drawing on the core elements of each tradition and weaving them together into a cohesive framework.

Core Components of the Hypothetical Religion

- Messianic Foundation (Second Temple Judaism)

- Central Figure: A divine Messiah, akin to the expected redeemer in Second Temple Judaism, who brings salvation and restores the world. This figure might be seen as both a human king (like David) and a cosmic savior, reflecting the eschatological hopes of the period (e.g., from texts like the Dead Sea Scrolls or Daniel).

- Monotheism with a Twist: While Second Temple Judaism emphasizes one God (Yahweh), the influence of Greek mythology and mystery religions might soften this into a henotheistic structure, where the Messiah is a divine emanation of the supreme God, surrounded by lesser divine beings or angels.

- Mystery Religion Elements

- Initiation and Secret Knowledge: Like the mystery cults, this religion would feature secretive rituals—perhaps a baptism or a symbolic death-and-rebirth ceremony (echoing Mithraism or the cult of Isis)—to grant adherents esoteric knowledge of the cosmos and their salvation.

- Sacramental Meals: Drawing from Dionysian rites or the Mithraic taurobolium (bull sacrifice), the religion might include a communal meal symbolizing unity with the Messiah, possibly involving wine (Dionysus) or bread (foreshadowing Christian Eucharist-like practices).

- Personal Salvation: The mystery religions’ focus on individual redemption would merge with Messianic Judaism’s communal restoration, creating a dual emphasis: personal enlightenment and the collective arrival of a utopian age.

- Greek Mythology Influence

- Pantheon Integration: The supreme God (Yahweh) could be equated with Zeus as a sky-father figure, while the Messiah might resemble a hero-god like Hercules or Apollo—born of divine and human origin, tasked with overcoming chaos (e.g., a Hades-like figure representing evil or death).

- Cosmology: The Greek concept of the cosmos, with its layers of heavens, earth, and underworld, might blend with Jewish apocalyptic visions (e.g., Enochic literature), creating a vivid multi-tiered universe populated by angels, demons, and mythological creatures like the Chimera or Hydra as agents of divine will or chaos.

- Oracular Practices: Inspired by the Oracle at Delphi, this religion might include prophetic figures or priestesses who channel divine messages from the Messiah or God, guiding followers through visions or riddles.

Beliefs and Practices

- Theology: The religion might teach that the Messiah, a semi-divine figure born of God and humanity, descended to earth to defeat a primordial serpent (combining the Jewish Satan with the Greek Typhon or Python) and usher in a golden age. After a sacrificial death (mystery cult influence), the Messiah ascends to the heavens, promising to return and judge the world.

- Rituals:

- A rite of passage involving a symbolic labyrinth (Greek Minotaur myth) where initiates confront their mortality, emerging “reborn” into the Messiah’s light.

- Festivals celebrating the Messiah’s victories, blending Jewish harvest feasts (like Sukkot) with Dionysian revelry—think processions with music, dance, and offerings of wine and grain.

- Ethics: A moral code combining Jewish law (e.g., the Ten Commandments) with Greek virtues (e.g., courage, wisdom, temperance), emphasizing loyalty to the Messiah and preparation for his return.

- Afterlife: A hybrid eschatology where the righteous join the Messiah in a celestial banquet (mystery cult reward) within a restored Eden-like earth (Jewish hope), while the wicked face a Tartarus-like underworld punishment (Greek influence).

Narrative Example

Imagine a sacred text describing the Messiah as “the Son of the Most High, clad in the armor of light, who wrestled the Leviathan of the abyss and bound it with chains forged by the heavenly smith (Hephaestus-like figure).” Initiates would reenact this battle in a subterranean temple, emerging to a hymn praising the Messiah’s triumph over death, celebrated with a feast of bread, wine, and olives under starlit skies.

Cultural Flavor

This religion would feel both familiar and exotic: the solemnity of Jewish temple worship infused with the ecstatic fervor of mystery rites and the poetic grandeur of Greek epic. Temples might resemble synagogues with added altars for offerings and statues of the Messiah depicted as a youthful warrior with a lyre (Apollo) or laurel crown (victory).

I then asked: Regarding this hypothetical religion, how similar is it to Christianity?

AI’s response…

This hypothetical religion—blending Second Temple Messianic Judaism, mystery religions, and Greek mythology—shares striking similarities with early Christianity, but also diverges in notable ways. Since Christianity itself emerged from Second Temple Judaism and developed within the Greco-Roman world, some overlap is inevitable. Let’s break it down by comparing key elements.

Similarities to Christianity

- Messianic Figure

- Hypothetical Religion: A divine-human Messiah who defeats evil, dies sacrificially, ascends to the heavens, and promises to return for judgment and restoration.

- Christianity: Jesus Christ, the Messiah, defeats sin and death through his crucifixion, rises from the dead, ascends to heaven, and will return to judge the living and the dead.

- Overlap: The core narrative of a savior figure with a redemptive mission and a second coming aligns closely with Christian theology. Both emphasize the Messiah as a bridge between God and humanity.

- Salvation and Eschatology

- Hypothetical Religion: Offers personal salvation through initiation and a collective utopian age, with a multi-tiered cosmos and an afterlife of reward or punishment.

- Christianity: Promises individual salvation through faith in Christ, culminating in a new heaven and new earth, with heaven for the righteous and hell for the damned.

- Overlap: The dual focus on personal redemption and cosmic renewal, plus a stratified afterlife, mirrors Christian eschatology, especially as it developed in the New Testament (e.g., Revelation).

- Rituals

- Hypothetical Religion: Features sacramental meals (bread and wine), initiation rites (symbolic death and rebirth), and festivals celebrating the Messiah’s victories.

- Christianity: Includes the Eucharist (bread and wine as Christ’s body and blood), baptism (death to sin, rebirth in Christ), and celebrations like Easter and Christmas.

- Overlap: The communal meal and initiation through a transformative ritual are strikingly similar to early Christian practices, which some scholars argue were influenced by mystery cults (e.g., Mithraism’s shared meals).

- Moral Framework

- Hypothetical Religion: Combines Jewish law with Greek virtues, emphasizing loyalty to the Messiah.

- Christianity: Builds on the Jewish Law (e.g., love God and neighbor) while adding virtues like faith, hope, and love, centered on devotion to Christ.

- Overlap: Both retain a Jewish ethical core while adapting it to a broader Greco-Roman audience.

Differences from Christianity

- Theological Structure

- Hypothetical Religion: Leans toward henotheism, with the Messiah as a divine emanation and lesser beings (angels, mythological figures) in a cosmic hierarchy.

- Christianity: Strictly monotheistic (Trinitarian), with Jesus as fully God and fully human, part of the Trinity, and no subordinate pantheon.

- Divergence: Christianity rejects the incorporation of other divine figures (e.g., Zeus, Apollo) and maintains a sharper distinction between God and creation, whereas this religion integrates Greek mythological elements more overtly.

- Cosmology and Mythology

- Hypothetical Religion: Features a vivid, multi-tiered cosmos with creatures like Leviathan or Typhon, and oracular practices inspired by Delphi.

- Christianity: While it includes angels, demons, and a cosmic battle (e.g., Satan in Revelation), it avoids the fantastical creatures and oracular traditions of Greek mythology, focusing instead on prophetic scripture.

- Divergence: The Greek mythological flair—labyrinths, serpentine chaos monsters, and priestesses—gives this religion a more eclectic, polytheistic texture absent in Christianity.

- Ritual Tone

- Hypothetical Religion: Emphasizes ecstatic, Dionysian revelry and elaborate symbolic reenactments (e.g., battling in a labyrinth).

- Christianity: Early rituals were simpler and more subdued (e.g., house church gatherings), evolving into formalized liturgy later, but lacking the theatrical mystery-cult intensity.

- Divergence: Christianity’s rituals, even with some mystery-cult parallels, prioritize solemnity and accessibility over secretive, esoteric spectacle.

- Cultural Context

- Hypothetical Religion: Fully embraces Greco-Roman aesthetics—temples with statues, laurel crowns, and epic poetry.

- Christianity: Initially resisted Greco-Roman paganism, though it later adopted some cultural forms (e.g., church architecture), while condemning idolatry and mythology.

- Divergence: This religion leans into Greek culture more enthusiastically, whereas Christianity maintained a tension with paganism, especially in its formative years.

How Close Is It?

This hypothetical religion could be seen as a parallel cousin to early Christianity—sharing a Messianic core, salvific rituals, and an eschatological hope—but with a more pronounced Greco-Roman flavor. It’s as if Christianity had fully embraced the mystery religions and Greek mythology rather than selectively adapting or rejecting them. For example:

- The Eucharist and baptism have parallels, but this religion’s labyrinthine initiations and oracular prophecies feel more like Mithraism or the Eleusinian Mysteries.

- The Messiah’s narrative echoes Jesus, but his depiction as a Hercules-like warrior with a lyre or crown leans into Greek heroism rather than the suffering servant of Isaiah 53.

In essence, it’s Christianity with the dial turned up on syncretism—less restrained by monotheistic boundaries and more infused with the theatricality and pluralism of its Hellenistic context. If early Christianity had taken this path, it might have looked like a mystery cult with Jewish roots and a Greek epic overlay, appealing to a broader Mediterranean audience but potentially losing its distinct identity over time.

When Did Judaism Begin? (Video)

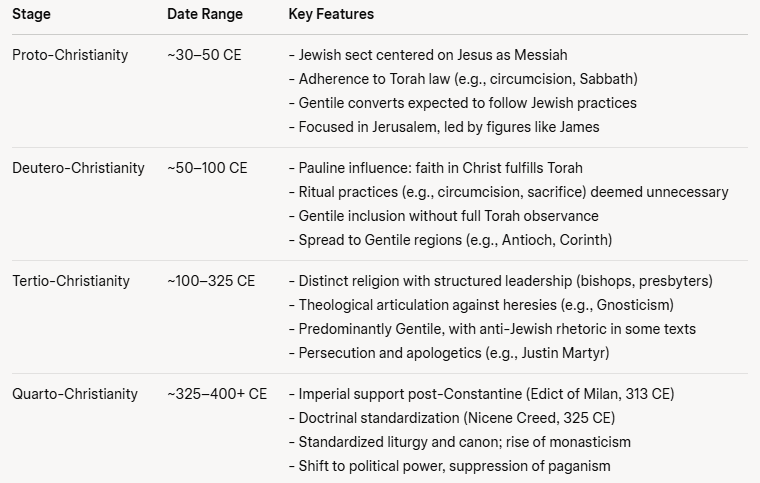

The Formation of Christianity

To understand the origins of Christianity, we must first look at Israel. The Bible—both the Old and New Testaments—is fundamentally a book about Israel. Additionally, the historical events that took place between these two testaments provide crucial context.

Since Christianity centers around Israel’s Messiah, it’s important to ask: What did the Israelites living during the second temple period expect from their coming Anointed One? What would his arrival bring? Their hopes can be summarized in at least five key expectations:

- The return of the exiles—not only those from Judah but also the scattered northern tribes. (Deut. 30:3; Isa. 11:11-13; Jer. 16:14-16, 30:3, 32:37; Ezek. 11:17, 36:24; Hos. 1:9-2:1, 2:23)

- The resurrection and reunification of Israel’s two houses, Judah and Ephraim (thus all twelve tribes). (Ezek. 37:1-22)

- The establishment of an Israelite theocratic kingdom with the Messiah as its ruler. (Ezek. 37:22-28; Hos. 1:9-11)

- A new ability for Israel to keep the law. (Deut. 30:8,10; Jeremiah 31:32; Ezekiel 11:19-20, 36:26-27, 37:24)

- Peace and justice for the nations under the Messiah’s divine rule. (Isa. 2:1-4; Mic. 4:1-4; Ps. 2:7-9; Isa. 11:1-4, 10; Dan. 7:13-14)

These expectations were not only held by Second Temple Jews but also shaped the beliefs of early Christians. This was the environment in which Christianity emerged.

The New Testament authors and apostles were not focused on promoting a new religion centered on individual salvation from hell. Instead, because Israel’s sins against Israel’s God had now been forgiven (Heb. 9:11-22), their primary concern was preparing all of Israel for the imminent return of their Messiah, the subsequent judgment, and the dawn of the Messianic age (Heb. 9:23-28).

Again, Christianity was not a new religion invented by Jesus, Paul, or anyone else—it was deeply rooted in Israelite traditions and eschatological expectations. In the first century it functioned as a Messianic movement within Judaism. The earliest Christians, primarily Jews, believed that Jesus had come first as a high priest, purifying Israel from sin once and for all. They awaited his return as a king who would gather the scattered exiles (the elect remnant) and establish an eternal Israelite theocracy.

But the waiting stretched on. As time passed, Christianity gradually became less Jewish* and more Greek. Yet, the faith continued to spread. Unlike the elite-driven religions and philosophies of the time, Christianity appealed to the common people. Jesus was a personal God—one who cared for the poor and disregarded social status. Masters and servants stood as equals before him. Outcasts found belonging in the Church.

As the movement grew, its leadership shifted. Educated men trained in Greek philosophy began to shape its theology, asking new questions about Jesus’ nature, often leading to division. With Constantine, Christianity transformed into a political force, institutionalized and formalized.

Thus, the faith that began as a Messianic hope among first-century Jews evolved into an empire-spanning religion. And it is to the Council of Nicaea that modern Christianity traces its doctrinal foundations.

*There is some speculation that Torah observant Christianity (anti-Pauline) later evolved into Islam.