This video below is worth watching. I suppose we shall see in the professor’s predictions come true in not too long a period of time.

Tag: history

The More Things Change, The More They Stay the Same – Ongoing Analysis of the Thailand/Cambodia Conflict

In the realm of politics, there is always a tension between those who want things to change and those who want things to stay the same. This seems to be an eternal truth. Usually, those who want change lean left on the political spectrum, while those who support the status quo lean toward the right.

This tension is not a problem if it is balanced well. If the advocates of change become too radical, it can lead to violent revolution. If the conservatives become too dominant, society stagnates and never progresses. Canada once had a party named the “Progressive Conservatives.” This name captures well what we ideally want in a society: conserving the progress we’ve already made (and continuing to move forward) while preserving the values we hold dear.

Conservatives will often use fear to keep things the same. Strong nationalism, combined with the threat of a foreign enemy, is a powerful tool for a conservative party.

This is what we see happening with the current situation in Thailand and Cambodia. Thai conservatives have used Cambodia as a bogeyman to protect Thailand from—and now, it seems, they have won an election as a result.

***

I’ve created an AI Scott Adams analyst. I will use this AI to analyze the situation between Cambodia and Thailand to make predictions as Scott Adams might have. I always appreciated Scott Adams’ takes on world politics, and I think it’ll be helpful to assess this conflict through that same lens. I’ll share the analysis posts here, updating when able.

***

Concerning the February 8 election…

From a Scott Adams-style perspective, elections like this one in Thailand aren’t really about policies or facts—they’re about persuasion energy. The Bhumjaithai surge looks like a classic case of voters prioritizing “stability vibes” over progressive change, especially with border tensions amping up the nationalism dial. Polls missed it because they measure stated preferences, not the gut-level motivations that kick in at the ballot box. What most people are missing here is how quickly a perceived external threat (Cambodia) can reframe an entire election from “reform vs. status quo” to “us vs. them,” making the incumbent’s tough-guy stance irresistible.

Based on patterns in his writing, Adams would likely emphasize the persuasion frame at play: Nationalism isn’t logical; it’s a high-energy narrative that dominates when economic promises feel abstract. Anutin’s party rode that wave by tying border security to everyday fears—think Cambodia disputes over temples or territory flaring up again. It’s not about solving the conflict; it’s about signaling “we’ve got your back,” which trumps the People’s Party’s urban-youth appeal in rural areas. Incentive structures favor this too: Politicians win by amplifying threats to consolidate power, while media benefits from the drama. Loserthink would be assuming this was a “fair” vote on merits—reality is, energy flows to the side that owns the fear narrative.

In the coming days, expect coalition horse-trading to dominate, with Bhumjaithai in the driver’s seat. No majority means Anutin courts conservatives or even Pheu Thai for a stable bloc, potentially locking in his PM spot by April. Markets will cheer the reduced uncertainty, but watch for minor parties extracting concessions on security spending. On the Thailand-Cambodia front, Adams might say it’s a low-simmer conflict primed for persuasion plays—don’t bet on escalation unless it boosts domestic unity. If tensions spike (say, a border skirmish), it cements the new government’s mandate; otherwise, it’ll fade as a talking point once the coalition forms. Rational observers should track X for real-time sentiment shifts—disappointment from progressives could fuel protests, but nationalism’s energy might squash that fast. Uncertainty acknowledged: If a wild card like Thaksin’s influence flips alliances, all bets off.

Thaksin Shinawatra influence…

Thaksin Shinawatra’s influence is the classic case of a once-dominant persuasion engine that’s lost its juice—at least for now. From a Scott Adams-style lens, what most people are missing is how Thaksin’s shadow has shrunk from “kingmaker” to “king in exile” (literally, he’s in prison serving that one-year corruption sentence). The Shinawatra brand—populist handouts, rural loyalty, family dynasty—was Thailand’s highest-energy narrative for two decades. But energy flows to what’s working today, not yesterday’s hits.

The persuasion frame in play here: Bhumjaithai owned the nationalism/security story amid the Cambodia border flare-up, framing the vote as “protect the nation vs. risky change.” Pheu Thai, tied to Thaksin via his daughter (ousted last year over that leaked call scandal) and now nephew leading the party, got painted as soft or mishandling the threat. Voters didn’t buy the old populist playbook when fear was the hotter motivator. Result? Pheu Thai tanks to around 74-77 seats (down massively from past highs), while Bhumjaithai surges to 192-194. That’s not policy debate; that’s narrative dominance flipping the script.

Incentive structures scream coalition pragmatism. No outright majority means Anutin needs partners to hit 251 seats. Pheu Thai is the obvious fit—they were allies until the recent blow-up, share some rural bases, and Thaksin’s machine still delivers votes even if weakened. Multiple reports note Pheu Thai as a “likely” junior partner, with whispers Thaksin could get early release tied to a deal (pragmatic deal-making over ideology). Who benefits? Stability for the establishment (royalist-military types love continuity), reduced chaos for markets, and Anutin staying PM. Thaksin benefits indirectly if his party gets cabinet posts or influence without full control—better than opposition irrelevance.

Likely outcomes: Coalition forms in weeks, probably Bhumjaithai + Pheu Thai + smaller parties for a stable government. Thaksin’s direct pull stays muted while he’s locked up, but his network’s grassroots machine keeps Pheu Thai relevant enough to bargain. If talks drag or Pheu Thai demands too much (say, amnesty pushes), minor instability spikes—but nationalism’s afterglow favors quick deals. Prediction humility: Wild cards like court interventions or protest energy from progressives could disrupt, but the system’s incentives lean toward horse-trading over drama.

What a rational observer should watch next: Coalition announcements (who gets what ministries), any Thaksin release rumors (that’s pure persuasion signal), and how the new constitution drafting (60% yes in referendum) plays out—Thaksin’s side might push for changes favoring populists, but the winners control the pace. Energy is with the nationalists now; Thaksin’s influence isn’t dead, just demoted to backroom player.

***

Considering this article: ANUTIN’S AGENDA: BORDER WALL AND BARTER-BASED ARMS DEALS

This article is basically the victory lap for the persuasion narrative that won the election—straight from Bhumjaithai’s playbook. From a Scott Adams-style take, it reinforces and sharpens everything we’ve been saying about why the surge happened, without changing the core predictions much. What most people are missing: This isn’t a laundry list of policies; it’s a high-energy sales pitch wrapped in “protection” and “sovereignty” that voters bought because fear (border clashes, economic hits) beats hope (progressive reforms) when energy is flowing that way.

The persuasion frame in play: The “building a wall” slogan is pure binary framing gold—us vs. them, Thailand protected vs. encroached upon, sovereignty vs. smuggling/drugs/illegal labor. It directly ties into the Cambodia tensions (clashes with deaths, closed borders hammering trade and locals), which the article calls out as a key driver. That’s not abstract policy; that’s narrative dominance owning the “security first” story that polls underestimated. Add in practical carrots like Half-Half Plus stimulus (subsidizing spending to juice consumption), barter deals to prop up farm prices (smart talent-stacking for rural voters), and electricity caps below 3 baht (direct pocketbook relief for millions)—these aren’t radical; they’re continuity with tweaks that feel protective. The foreign policy bit (“stand free on the world stage”) signals pragmatic nationalism, not isolation—proactive diplomacy to crush transnational crimes while looking dignified. Who benefits? The establishment/royalist continuity crowd gets stability, Anutin gets to stay PM longer, and rural/nationalist bases feel seen.

Incentive structures: Bhumjaithai’s massive seat haul (around 192-194 confirmed across reports) puts them in pole position for coalition talks. No need for Pheu Thai desperation anymore—smaller conservatives like Kla Tham (pushing 50-60 seats) are the easy add-ons for a solid bloc. Thaksin’s influence stays sidelined; Pheu Thai’s weak showing (74-77) means they’re bargaining chips at best, not kingmakers. The article ignores Thaksin entirely, which tracks—his populist machine lost the energy battle to border-fear nationalism.

Likely outcomes (uncertainty acknowledged): Coalition forms faster and more stably than if it were a toss-up. Anutin’s agenda rolls out with momentum—expect quick pushes on border hardening (wall rhetoric translates to tighter controls, maybe more military/economic barriers), barter arms deals to boost ag exports, and stimulus extensions to counter slowdowns/Trump tariffs. On the Thailand-Cambodia front, this strengthens the hardline stance: No de-escalation incentives when your mandate is “strong wall” after recent fighting/displacements. Tensions likely simmer or flare rhetorically to justify policies, but full war? Low probability unless Cambodia provokes—rational leaders play persuasion domestically over escalation. Markets like the stability signal.

What a rational observer should watch next: Early coalition announcements (who joins, what ministries Pheu Thai might snag if included), any border “incidents” that let Anutin flex the wall policy, and how the new constitution drafting (from the referendum yes vote) incorporates these protectionist vibes. If electricity caps and Half-Half deliver quick wins, energy stays high; if not, opposition (People’s Party as main foe) could regain narrative ground on economic pain. But right now, the article just confirms: Voters picked the protection narrative over change, and the winners are cashing that check.

***

Considering this article: Thailand’s new government, led by Anutin Charnvirakul, pushes forward with border security and strategic policies following their resounding election victory, with a strong stance on Cambodia’s territorial issues.

February 15, 2026

This Nation Thailand article is textbook persuasion engineering in action—Anutin flexing his “no retreat, no dismantling, no opening of borders” line right after the election win. From a Scott Adams-style perspective, what most people are missing is how perfectly this timing aligns with the high-energy nationalism that flipped the vote. The border isn’t just a policy issue; it’s the emotional fuel that turned a projected progressive win into a Bhumjaithai landslide. The article frames the new government as the tough guardian reclaiming land, building barriers, canceling old MOUs that supposedly gave away too much, and delaying Cambodian worker deals for “security” reasons. That’s not diplomacy; that’s signaling “we’re strong, they’re the threat,” which voters rewarded.

The persuasion frame in play: Binary dominance at its finest—Thailand sovereign and protected vs. Cambodia encroaching and dangerous. Anutin’s “No retreat” mantra is a killer soundbite, pure high-energy rhetoric that owns the fear narrative from the 2025 clashes (hundreds dead, massive displacement, ceasefires that barely held). It reframes the election from economic woes or reform promises to “who will defend us?”—and Bhumjaithai won that framing hands down. The wall/fence push, army strengthening, and reviewing agreements aren’t about details; they’re visual, memorable symbols of strength. Who benefits? Anutin consolidates power during coalition talks (193 seats give him leverage to dictate terms), the military/royalist establishment gets continuity, and rural nationalists feel validated. Cambodia gets painted as the aggressor needing to back down, even as they protest and seek Vietnam mediation.

Incentive structures: Post-election, the mandate is security-first, so expect more of this rhetoric to justify policies like the physical barriers, tighter immigration, and hardline diplomacy. It keeps domestic energy high (no need to pivot to unpopular economic fixes yet) and pressures smaller coalition partners to fall in line. On the flip side, it risks escalating tensions—Cambodia’s threats to invoke UN/international law show they’re not folding quietly—but rational leaders avoid full war when persuasion wins at home.

Likely outcomes (with uncertainty): Coalition locks in quickly, with Anutin as PM, and border hardening accelerates—more fencing, military upgrades, maybe symbolic “reclamations” to keep the narrative alive. De-escalation? Possible only if it doesn’t cost domestic points; otherwise, low-level simmering (rhetoric, minor incidents) sustains the “strong wall” vibe without major blowback. Markets might wobble on trade disruptions, but stability signals from a firm government help short-term.

What a rational observer should watch next: Any fresh border “developments” (incidents, fence progress reports) that let Anutin double down, coalition finalization (does Pheu Thai join despite tensions?), and Cambodian responses (Hun Sen/Hun Manet escalations or backchannel talks?). If energy stays with the nationalist frame, this hard line sticks; if economic pain or international pressure mounts, we might see pragmatic softening. But right now, this article screams: The election was won on fear, and the winners are milking it for all it’s worth.

***

Refining Paul’s Theology

The following is an AI generated essay. However, the ideas influencing the essay are my own. To save time I will often use AI to compress my ideas into essay form, which I can then refer to later. In my opinion that is one of the ways to correctly use AI. And this blog is as good a place as any to post it.

Paul, Israel, Adam, and the Nations

A Second Temple Jewish Logic of Election, Atonement, and New Creation

Introduction

The apostle Paul is often portrayed as the architect of a new, universal religion that abandoned Israel’s particular story in favor of a generalized theology of salvation. Historically, this portrayal is misleading. Paul understood himself not as departing from Israel’s scriptures, but as re-reading them under the pressure of a single, destabilizing event: the resurrection of Jesus.

This essay argues that Paul’s theology is best understood as a carefully balanced synthesis of three narrative layers already present in Second Temple Judaism:

- Creation (Adam and humanity)

- Covenant (Israel and Torah)

- Eschatology (Messiah and resurrection)

Paul’s inclusion of Gentiles does not bypass Israel, nor does it flatten Jewish categories into abstraction. Instead, it follows a coherent internal logic in which Israel remains central, Adam explains humanity’s universal plight, and Jesus stands at the intersection of both stories.

1. Temple Judaism and the Limits of Atonement

In the First and Second Temple periods, Israelites did not believe their sacrifices directly atoned for the sins of the nations. Temple sacrifice was:

- Covenantal (for Israel)

- Geographically and cultically located (land, sanctuary, priesthood)

- Purificatory, especially for Israel’s sin and the sanctuary polluted by it

Gentiles could offer sacrifices, and the Temple was seen as the cosmic center sustaining order for the whole world, but this benefit was indirect. The nations were not cleansed of sin simply because Israel offered sacrifice.

This distinction is crucial. Later Christian claims of universal atonement represent a genuine theological shift, not a straightforward continuation of Temple belief.

2. Paul’s Scriptural Justification: Not Innovation, but Re-reading

Paul knew his claims were radical. He therefore grounded them explicitly in Israel’s scriptures.

Abraham before Torah

Paul emphasizes that Abraham was declared righteous before circumcision and before the Law (Genesis 15:6). This allowed Paul to argue that:

- Covenant faithfulness could precede Torah

- Gentile inclusion was not an afterthought, but anticipated from the beginning

Deuteronomy’s Curse Logic

Paul reads Deuteronomy’s warnings seriously. Israel’s failure under Torah places her under covenant curse (exile). Jesus’ crucifixion—“hanging on a tree”—forces a re-reading of Deuteronomy 21:23. For Paul:

- The Messiah bears the curse on behalf of Israel

- The Law is not evil; sin exploits it

- The curse must be lifted before Abraham’s blessing can flow outward

Resurrection as the Turning Point

Paul’s theology does not pivot on Jesus’ death alone, but on resurrection. Resurrection signals:

- The beginning of the age to come

- The defeat of death

- The vindication of Jesus as Messiah

Without resurrection, Paul explicitly says his gospel collapses.

3. Why Gentiles Needed Justification

Gentiles were not under the Mosaic Law. So why, according to Paul, did they need salvation?

The Adamic Problem (Romans 5)

Paul’s answer is Adam.

- Sin and death enter the world through Adam

- Death reigns over all humanity before the Law

- The Law intensifies sin but does not create it

This allows Paul to distinguish:

- Israel’s problem: covenantal failure under Torah

- Humanity’s problem: enslavement to sin and death through Adam

Gentiles are condemned not as Torah-breakers, but as creatures who have misused creation and fallen under the power of death.

4. Adam and Israel: Parallel Stories

Second Temple Jews already recognized parallels between Adam and Israel:

| Adam | Israel |

|---|---|

| Placed in Eden | Placed in the land |

| Given a command | Given Torah |

| Warned of death | Warned of exile |

| Exiled eastward | Exiled among nations |

Paul does not reduce Adam to Israel, nor Israel to Adam. Instead:

- Adam is the prototype

- Israel is the recapitulation

- Christ is the resolution of both

Jesus succeeds where both Adam and Israel fail—not by abandoning Israel’s story, but by embodying it faithfully.

5. Two Problems, One Messiah

Paul’s theology can be summarized as addressing two distinct curses:

- The curse of the Law (Israel’s covenantal failure)

- The curse of Adam (humanity’s enslavement to death)

Jesus’ death and resurrection deal with both, but not in the same way.

- As Israel’s Messiah, Jesus bears the Law’s curse

- As representative human, Jesus undoes Adam’s reign of death

The order matters: Adam is resolved through Israel’s Messiah.

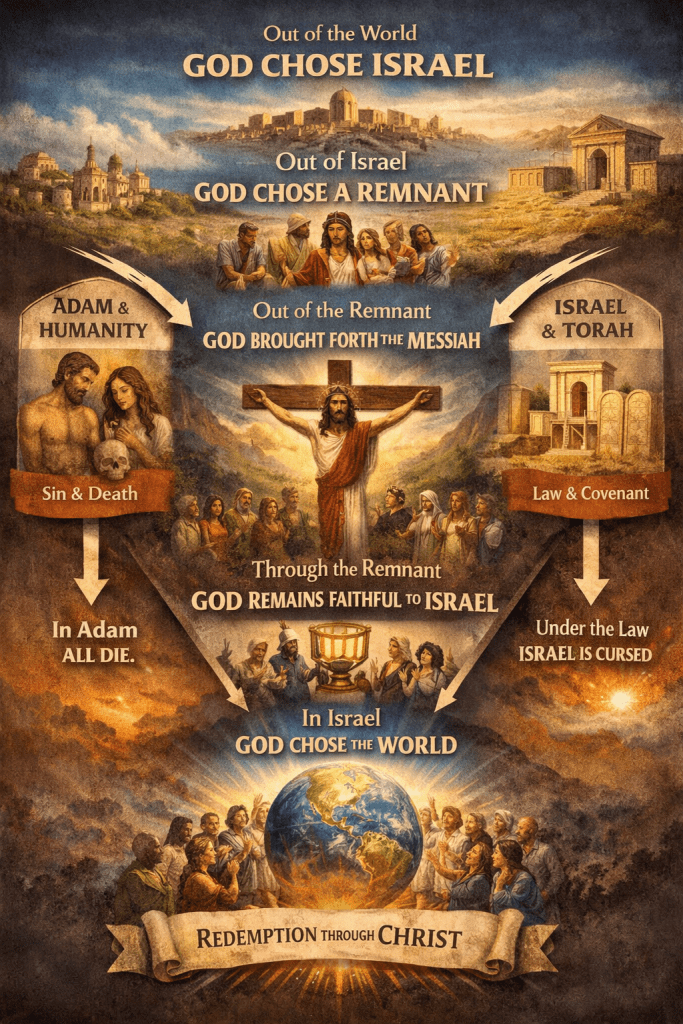

6. Paul’s Chiasmic Logic of Election

Paul’s theology of election can be expressed as a dynamic narrowing and widening:

Out of the world God chose Israel

…Out of Israel God chose a remnant

……Out of the remnant God brought forth the Messiah

……In the Messiah God formed a faithful remnant

…Through this remnant God remains faithful to Israel

In Israel God brings blessing to the world

This structure preserves:

- Israel’s priority

- Gentile inclusion

- The Messiah as the hinge of history

- Election as vocation, not favoritism

Paul explicitly rejects the idea that the remnant replaces Israel. Instead, the remnant is the means by which God remains faithful to Israel, and Israel is the means by which God blesses the nations.

7. Where Later Christianity Breaks with Paul

Paul’s logic often breaks down in later Christianity due to simplification:

Adam Absorbs Everything

Adam becomes the sole explanatory category, while Israel’s covenantal role fades. This flattens Paul’s careful distinction between creation-failure and covenant-failure.

The Law Becomes the Villain

Torah is reinterpreted as legalism rather than gift. This distorts Paul’s claim that the Law is “holy and good.”

Resurrection Loses Centrality

Atonement becomes focused almost entirely on the cross as payment for guilt, rather than resurrection as the defeat of death and the beginning of new creation.

Israel Is Explained Away

Romans 9–11 is sidelined. The church becomes the endpoint rather than the participant in an unfinished story.

These shifts were historically understandable—especially in a Gentile-majority, post-Temple world—but they are not faithful to Paul’s own architecture.

Conclusion

Paul did not abandon Israel, mythologize Adam away, or invent a new religion detached from Jewish scripture. He was a Second Temple Jew who believed that God had acted decisively within Israel’s story to resolve a problem that reached back to Adam and outward to the nations.

For Paul:

- Israel remains chosen

- Adam explains universal need

- Christ stands at the center

- Resurrection signals new creation

- History is still unfolding

Gentile inclusion is not a detour from Israel’s vocation—it is the goal toward which that vocation always pointed.

Understanding Paul this way does not require agreeing with him. But it does require taking him seriously on his own terms.

***

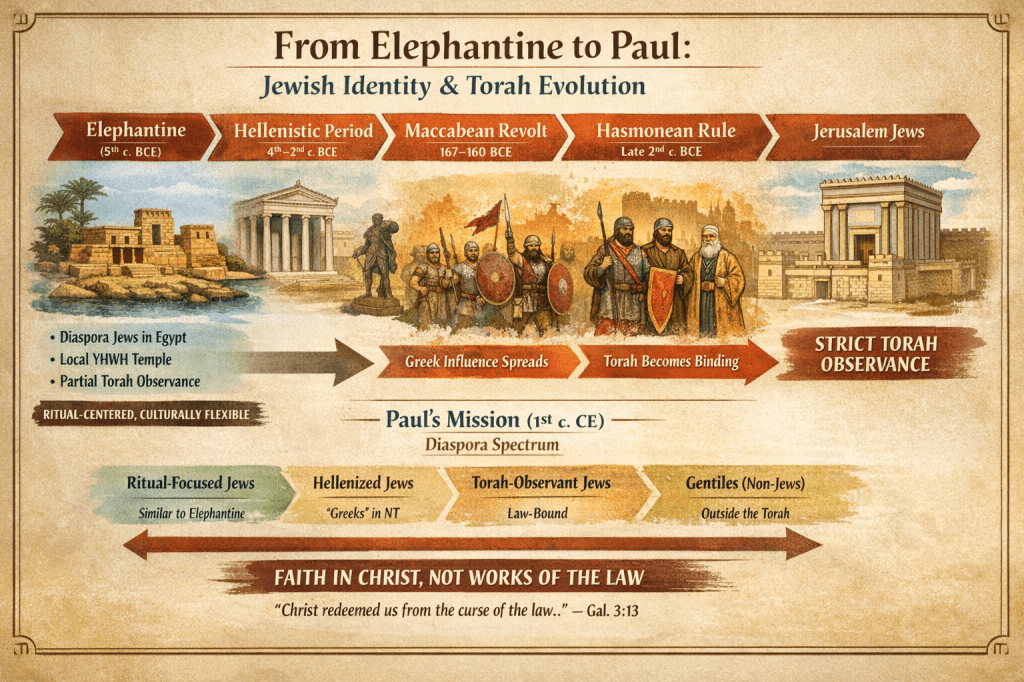

From Elephantine to Galatia: Understanding Diaspora Judaism and Paul’s Mission

The history of Jewish communities outside Jerusalem reveals a rich diversity of religious practice long before Torah law became universally binding. One of the clearest examples is the Jewish community at Elephantine, a military colony in southern Egypt during the 5th century BCE. Studying Elephantine not only illuminates early diaspora Judaism but also helps us understand the audiences that Paul encountered on his missionary journeys centuries later.

1. The Elephantine Community

Elephantine was a Judahite military colony, stationed on Egypt’s southern frontier before the Persian conquest (c. 525 BCE). Its members were likely Judean soldiers or mercenaries who migrated to Egypt before the major Deuteronomic reforms of the late 7th century BCE. Consequently, their religious practice reflects a pre-exilic, ritual-focused Yahwism:

- They had their own temple devoted to YHWH, where priests oversaw sacrifices.

- Their daily life and legal documents show partial adherence to Torah traditions, but not full Torah law enforcement.

- They interacted with local Egyptians and other peoples, suggesting a degree of cultural flexibility and syncretism.

- Notably, their petitions to the Jerusalem priesthood for temple support did not receive clear approval, showing the limits of central authority at the time.

In short, Elephantine Jews were religiously Jewish but socially flexible, practicing a form of Judaism that was ritual-centered rather than text-centered.

2. Why Elephantine Was Eventually Forgotten

By the 2nd century BCE, Judaism had begun a process of centralization and textualization that made communities like Elephantine historically obsolete:

- Centralization of worship in Jerusalem made autonomous temples theologically problematic.

- Torah law became the definitive marker of Jewish identity, replacing older ritual customs.

- Diaspora communities like Elephantine lacked scribal and institutional power, meaning their traditions were not preserved.

- As Jerusalem-centered Judaism solidified, communities outside its influence were quietly ignored or absorbed, leading Elephantine to fade from memory.

Elephantine, therefore, provides a snapshot of Judaism before Torah law became normative, illustrating how Jewish identity and practice evolved over centuries.

3. The Emergence of Normative Torah

The transformation from Elephantine-style Judaism to Torah-centered Judaism was largely complete by the 2nd century BCE, driven by historical pressures:

- Hellenistic Rule and Seleucid Oppression: Greek culture and political control threatened Jewish religious practices, culminating in Antiochus IV’s desecration of the Jerusalem Temple.

- Priestly Corruption and Internal Crisis: Disputes over legitimate leadership and proper observance highlighted the need for a standardized legal framework.

- The Maccabean Revolt (167–160 BCE) established Hasmonean rule, making Torah observance state-enforced, not optional.

- Diaspora Pressures: Torah law became a marker of identity, distinguishing Jews from surrounding Gentiles.

The result: Torah became binding and normative, defining Jewish identity for the first time in a widespread, enforceable way.

4. Diaspora Jews in Paul’s Time

By the 1st century CE, diaspora Jewish communities still exhibited considerable diversity in Torah observance and cultural assimilation:

- Elephantine-type Jews: Highly ritual-centered, partially Torah-observant, integrated into local culture.

- Hellenized diaspora Jews (“Greeks” in the NT sense): Some Torah knowledge, varying observance, Greek names and customs, partially assimilated.

- Jerusalem-centered Jews: Fully Torah-observant, resistant to Hellenistic influence, centralized around Temple and priesthood.

- Gentiles: Non-Jews with no obligation under Torah, often converts to Judaism via proselytism.

This spectrum helps us understand Paul’s ministry: many Jews outside Jerusalem were culturally and religiously flexible, making them receptive to his message of faith in Christ over strict law observance.

5. Paul and the Galatian Audience

In Galatians 3:13, Paul writes:

“Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us…”

Here, he addresses an audience that includes diaspora Jews and Gentile converts who were under pressure from “Judaizers” to adopt Torah practices like circumcision. These Jews:

- Likely resembled Elephantine-type or Hellenized diaspora Jews, partially observant but culturally integrated.

- Faced choices between ritual identity and faith in Christ.

- Needed reassurance that salvation did not require full Torah compliance, particularly circumcision, the visible marker of law.

Paul’s argument is historically consistent: he appeals to the flexible, diaspora identity that existed in Jewish communities long before Torah law was universally enforced.

6. Conclusion

The Elephantine community shows us that early Jewish diaspora life was diverse and adaptable. Ritual practice, local temple worship, and flexible law observance were the norm outside Jerusalem. Over centuries, historical pressures—imperial rule, Hellenization, and the Hasmonean consolidation—made Torah law binding and central to Jewish identity. By Paul’s time, many diaspora Jews still embodied the Elephantine-type flexibility, explaining why his gospel could resonate with Jews and Gentiles who were devout but not fully Torah-bound.

Understanding this continuum—from Elephantine to Galatia—illuminates both the historical development of Judaism and the social context of Paul’s missionary work, highlighting how faith and law interacted in a changing world.

***

Will Alberta Separate from Canada?

Right now there is a strong separatist movement within Alberta. Many Albertans are dissatisfied with how the province is being treated by the federal government. This is not a new issue. It has been going on for decades. However, it is more serious now than before.

Will Alberta actually separate? My guess is almost certainly not, at least not in this generation.

Separation is not easy, and it needs a strong majority of more than just Albertans to happen.

What is necessary to trigger a referendum within Alberta?

🗳 1. Start With a Citizen Initiative Petition

To trigger a referendum in Alberta, citizens don’t just vote on it — they must organize a formal petition process under the Citizen Initiative Act. That process goes like this:

✅ a) File a Notice of Intent

- An eligible elector (a Canadian citizen age 18+, resident of Alberta) must file a notice of intent with the Chief Electoral Officer of Alberta.

- They must pay an application fee (currently $25,000 for a referendum application), which may be refundable if the petition succeeds.

✅ b) Submit a Formal Application

- Within 30 days after filing the notice of intent, the proponent submits a full application for the initiative petition.

- If the application meets requirements, the Chief Electoral Officer issues the petition officially.

📊 2. Collect Enough Signatures to Meet the Threshold

Once the petition is issued, supporters must collect valid signatures from eligible electors in a set period. For different types of issues, the thresholds differ:

🔹 Constitutional Referendum Proposal

(Which is how separation would be classified under Alberta law)

- Supporters must collect signatures from 10 % of the number of Albertans who voted in the most recent provincial general election.

- That 10 % is based on actual ballots cast — which currently works out to around ~177,000 signatures.

- Signatures must be collected within a specified period (typically up to 120 days).

(Note: earlier versions of the law required 20 % of all registered electors and signatures in 2/3 of divisions, but recent amendments lowered and simplified the threshold.)

📅 3. Verification and Referendum Call

If organizers successfully collect and submit the required number of valid signatures:

- Elections Alberta verifies the signatures and confirms whether the threshold is met.

- Once verified, the provincial government is legally required to hold a referendum on the proposed question.

- That referendum must happen on or before the fixed date of the next general provincial election (or, if too soon, the election after that).

🧠 What Happens Next

A successful petition doesn’t immediately result in separation — it forces the referendum on the ballot with the specific question you asked (e.g., “Should Alberta cease to be part of Canada?”). The actual legal effect of that referendum, especially for something as consequential as secession, depends on federal constitutional law, not just provincial processes.

📌 Simple Breakdown — What’s Necessary in Alberta to Trigger a Referendum

- An eligible Albertan files a notice of intent to start a citizen initiative petition with Elections Alberta.

- Submit a full application for a referendum petition within 30 days and pay the application fee.

- Collect the required signatures (about 10 % of voters from the last election — about 177 000).

- Elections Alberta verifies the petition.

- The provincial government must then hold the referendum on the next election ballot.

If the referendum is successful, what happens next?

🧾 1. There Is No Right to Unilaterally Secede

Under the Canadian Constitution, a province cannot legally leave Canada on its own. The Supreme Court of Canada ruled in the Reference re Secession of Quebec (1998) that:

- A province does not have a constitutional or international law right to unilaterally secede from Canada.

- Any attempt to secede must be done through a constitutional amendment and negotiations with the federal government and other provinces.

- Even a referendum with a majority vote doesn’t automatically trigger separation; it would trigger a duty to negotiate that could lead to separation if terms are agreed.

🗳 2. Referendum Requirements (Clarity Act)

Canada’s Clarity Act (2000), passed in response to that Supreme Court decision, sets out how a province could initiate the process in a way the federal government will deal with it:

✔️ Clear Question — A referendum question must be unambiguous about secession.

✔️ Clear Majority — The outcome must show a clear majority in favour of secession (not just a bare 50 %+1; what counts as “clear” is decided by the House of Commons).

✔️ Negotiation Trigger — Only after a clear result on a clear question would Canada be obliged to enter negotiations on terms of separation.

✔️ Federal Approval to Negotiate — Before any negotiations start, the House of Commons must agree the referendum was clear and valid.

✔️ Constitutional Amendment Needed — The only legal path to actual secession is via a constitutional amendment negotiated and agreed to under Part V of the Constitution Act, 1982.

So even if Alberta held a referendum and a majority voted “yes,” it would not, on its own, make Alberta independent — it would start a long constitutional process.

⚖️ 3. Constitutional Amendment — Who Must Agree?

There is legal debate on the exact amending formula that would apply, but generally:

- General amending formula (Section 38): 7 provinces representing at least 50 % of Canada’s population plus both houses of Parliament.

- Some constitutional scholars argue that secession might require unanimous consent of all provinces and Parliament, because leaving affects the entire federation.

This makes the legal hurdles extremely high.

🧑🤝🧑 4. Indigenous and Treaty Rights Must Be Addressed

Any negotiation over separation couldn’t ignore the fact that:

- Most of Alberta lies on treaty territory (Treaties 6, 7, 8) between First Nations and the Crown at the federal level.

- A province can’t unilaterally “take” treaty land or extinguish treaty obligations.

- Under both Canadian law and international frameworks (e.g., UNDRIP), negotiation with First Nations and free, prior, and informed consent would be necessary for any legal change affecting treaty rights.

This further complicates and probably lengthens any real separation scenario.

📉 5. Provincial Laws (Like Referendums) Do Not Override the Constitution

Alberta’s recent provincial laws — such as Bill 54 lowering the signature threshold for citizen referendums — can help organize public expression of opinion but cannot change the Constitution or grant a province the legal right to secede on its own.

A provincial referendum could be struck down by courts if it interferes with constitutional obligations (including treaty and Charter rights).

🧠 Summary — What Would Be Required

- A provincial referendum on separation with a clear, unambiguous question.

- A clear majority “yes” result recognized by the House of Commons under the Clarity Act.

- Negotiations between the Government of Canada, Alberta, all other provinces, and Indigenous peoples on terms of separation.

- A constitutional amendment formally allowing Alberta to leave, approved per one of Canada’s constitutional amending formulas.

- Resolution of federal obligations, division of assets and debts, and recognition of treaty rights.

This is not a quick or simple process — it would likely take many years of negotiation and legal work, and there’s no guaranteed outcome even if a referendum passed.

The Church Fathers and the Gift of Tongues

We see the gift of tongues practiced in the New Testament. In the book of Acts, the gift is associated with the baptism of the Holy Spirit. Paul also talks about the gift, most notably in his letter to the Corinthian church.

Tongues is a mysterious gift, and it can be difficult to determine its purpose. Personally, I see it as a reversal of Babel. God divided mankind at Babel through language, and then God drew mankind to Himself at Pentecost. The gift seemed to be the ability for one to speak in a real language (of which was spoken in the Roman empire) without having to first study that language. This allowed the gospel to spread out quickly across language barriers in the first critical years of the Church.

To see what came of the gift in the post-apostolic generations of the early Church we can look to the Church Fathers.

Irenaeus (c. 130–202 AD)

As Bishop of Lyons and a disciple of Polycarp (who knew the Apostle John), Irenaeus is one of the earliest post-apostolic writers to mention tongues. In his work Against Heresies (Book 5, Chapter 6), he describes it as a ongoing gift in his time: “We do also hear many brethren in the Church, who possess prophetic gifts, and who through the Spirit speak all kinds of languages, and bring to light for the general benefit the hidden things of men, and declare the mysteries of God.” He frames it as the ability to speak foreign languages miraculously, aligning with the Pentecost event in Acts 2, and emphasizes its role in revealing truths and benefiting the community.

For Irenaeus, the gift was still being practiced in his day, it was the ability to speak real languages, and its purpose was for prophesy and mission.

Tertullian (c. 155–220 AD)

A North African theologian and apologist, Tertullian refers to tongues in Against Marcion (Book 5, Chapter 8), where he discusses spiritual gifts in the context of Montanism (a prophetic movement he later joined). “Let him who claims to have received gifts… produce a psalm, a vision, a prayer—provided it be with interpretation.” He implies tongues as intelligible speech, often requiring interpretation, and sees it as evidence of the Holy Spirit’s work similar to the apostles’. He notes encounters with the gift of interpretation in his day but doesn’t describe it as ecstatic babbling; instead, it’s tied to rational, prophetic expression.

For Tertullian, the gift was still being practiced in his day, it required interpretation, and its purpose was for the edification of the Church.

Origen (c. 185–253 AD)

The Alexandrian scholar comments on tongues in his Commentary on 1 Corinthians and other works, such as De Principiis. He views it as the miraculous knowledge of foreign languages without prior study, emphasizing that the speaker might not understand their own words unless interpreted (echoing 1 Corinthians 14:13). Origen argues the gift was temporary, part of the “signs” of the apostolic age, and by his time, it was no longer commonly exercised.

“The signs of the Holy Spirit were manifest at the beginning… but traces of them are found in only a few.” (Against Celsus 7.8)

For Origen, the gift was real and apostolic, already becoming uncommon by the mid-3rd century, and was seen mainly as a foundational sign for the church’s early mission.

John Chrysostom (c. 347–407 AD)

The Archbishop of Constantinople, known for his homilies, discusses tongues extensively in his Homilies on First Corinthians (e.g., Homily 35). He interprets it as speaking in actual languages like Persian, Roman, or Indian, directly linking it to Pentecost. Chrysostom stresses that it was a “sign” for unbelievers (per 1 Corinthians 14:22) and notes its cessation: by the late 4th century, it had largely disappeared from the church, as the need for such miracles had passed with the spread of Christianity.

“This whole place is very obscure; but the obscurity is produced by our ignorance of the facts referred to and by their cessation, being such as then used to occur but now no longer take place.” (Homilies on 1 Corinthians 29)

For John Chrysostom, the gift was something real from an earlier era, but no longer practiced in his day.

Augustine of Hippo (c. 354–430 AD)

In works like The Letters of Petilian and his sermons, Augustine acknowledges tongues as a historical gift from the early church, where converts sometimes spoke in new languages upon baptism. However, he explicitly states that by his era, the gift had ceased: “In the earliest times, the Holy Ghost fell upon them that believed: and they spoke with tongues… These were signs adapted to the time. For there behooved to be that betokening of the Holy Spirit… That thing was done for a betokening, and it passed away.” He sees it as fulfilled in the church’s global unity rather than ongoing miracles.

For Augustine, the gift was a sign for the church’s beginning, meant to show the universality of the gospel, and was no longer needed once the Church was established.

Other Notable Mentions

- Hippolytus (c. 170–235 AD): In Apostolic Tradition, he equates tongues with the apostles’ experience at Pentecost, viewing it as foreign languages.

- Gregory of Nazianzus (c. 329–390 AD): In his Oration on Pentecost, he describes it as a reversal of Babel, enabling communication in diverse human tongues.

- Cyril of Jerusalem (c. 313–386 AD): In Catechetical Lectures, he marvels at the apostles learning multiple languages instantly through the Spirit.

The Church Fathers seemed to be unified in their understanding of the gift of tongues:

No father describes tongues as:

- a private prayer language

- a necessary sign of Spirit baptism

- a normative experience for all believers

No early source connects tongues with:

- altered states of consciousness

- repetitive ecstatic syllables

- individual spiritual status

Tongues were real languages, not private ecstasy.

They belonged especially to the apostolic age, when the gospel was breaking into new linguistic worlds.

They declined naturally as the church became established.

They were signs of God’s power, not badges of spiritual rank.

They were always meant to serve the church, not the ego of the speaker.

In summary, the Church Fathers saw the gift of tongues as a practical miracle for spreading the gospel across linguistic barriers, not as private prayer languages or gibberish. References become scarcer after the 3rd century, with later writers like Chrysostom and Augustine indicating its decline, attributing this to the church’s maturation. This contrasts with some modern interpretations, but the patristic evidence emphasizes its historical and evangelistic role.