In this space I am going to store research concerning all things Hebrew Scriptures, focusing much on the Masoretic Text (MT) and the Septuagint (LXX): videos, articles, essays, Dead Sea Scroll (DSS) research, AI research, etc… So, if you are studying the MT and/or the LXX, and you’ve stumbled across this post, I hope you find something useful.

***

***

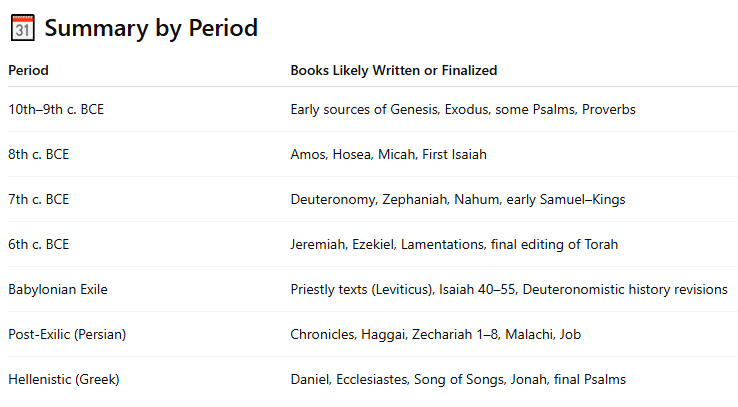

Dating the Scriptures (AI Research – Grok, ChatGPT, and Claude)

Torah (Pentateuch)

The first five books—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy—are traditionally attributed to Moses but are now understood by most scholars as composite works from multiple sources (Yahwist, Elohist, Priestly, and Deuteronomic) compiled over centuries. Final redaction likely occurred during or after the Babylonian Exile (6th century BCE).

- Genesis: Likely compiled in its current form during the Persian period (538–332 BCE), though it incorporates earlier oral and written traditions from the 10th–6th centuries BCE. The creation stories, patriarchal narratives, and flood accounts reflect ancient Near Eastern motifs, with some elements possibly dating to the early monarchy (10th century BCE). The final shaping likely occurred post-Exile to address the needs of the returning community.

- Exodus: Composed over time, with narrative cores (e.g., the Exodus event, covenant at Sinai) possibly rooted in 13th–10th-century BCE traditions. The Priestly and Deuteronomic elements were likely added during the 7th–5th centuries BCE, with final redaction in the Persian period (5th century BCE).

- Leviticus: Primarily a Priestly work, likely composed between the 6th and 5th centuries BCE during or after the Exile, though some ritual laws may reflect earlier practices (8th–7th centuries BCE). Its focus on purity and temple worship suggests a post-Exilic context.

- Numbers: A composite text with narrative and legal material, likely compiled in its final form during the Persian period (538–332 BCE). It incorporates earlier traditions, such as wilderness wanderings and census accounts, potentially from the 10th–7th centuries BCE, with Priestly and Deuteronomic additions in the 7th–5th centuries BCE. The final redaction reflects post-Exilic concerns about community identity and land allocation.

- Deuteronomy: Likely composed in stages, with a core tied to the reforms of King Josiah (late 7th century BCE, c. 622 BCE), based on its alignment with the “Book of the Law” found in 2 Kings 22:8–10. Additional material was added during the Babylonian Exile (597–538 BCE) and finalized in the Persian period (5th century BCE). Its covenantal theology and legal code reflect both pre-Exilic and post-Exilic contexts.

Nevi’im (Prophets)

The Nevi’im include the Former Prophets (historical narratives: Joshua – 2 Kings) and Latter Prophets (prophetic oracles: Isaiah – Malachi). The Former Prophets form part of the Deuteronomistic History (DtH), likely compiled during the Babylonian Exile (6th century BCE) with earlier sources. The Latter Prophets’ dates are tied to the historical periods of the named prophets, though redaction often occurred later.

- Joshua: Part of the Deuteronomistic History, compiled in the 6th century BCE during the Exile. It incorporates earlier traditions about the conquest of Canaan (potentially 13th–10th centuries BCE), but its final form reflects Exilic theology, emphasizing obedience to the covenant.

- Judges: Also part of the Deuteronomistic History, finalized c. 6th century BCE. Stories of the judges likely stem from oral traditions of the pre-monarchic period (12th–11th centuries BCE), but the text’s structure and theological framing suggest Exilic redaction.

- 1 Samuel: Part of the Deuteronomistic History, compiled c. 6th century BCE. It includes traditions about Samuel, Saul, and David from the early monarchy (11th–10th centuries BCE), redacted to emphasize divine kingship and covenant fidelity.

- 2 Samuel: Continues 1 Samuel, part of the Deuteronomistic History, finalized c. 6th century BCE. It draws on court records or oral traditions about David’s reign (10th century BCE), shaped by Exilic concerns about leadership and divine judgment.

- 1 Kings: Part of the Deuteronomistic History, compiled c. 6th century BCE, with possible updates in the Persian period. It incorporates royal annals and temple records from the monarchic period (10th–7th centuries BCE), framed to explain the Exile as divine punishment.

- 2 Kings: Completes the Deuteronomistic History, finalized c. 6th century BCE, with a possible secondary redaction (Dtr2) post-562 BCE to account for Judah’s fall. It uses earlier sources from the divided monarchy (9th–7th centuries BCE).

- Isaiah: A composite work spanning centuries. Chapters 1–39 (First Isaiah) are largely from the 8th century BCE (c. 740–700 BCE), attributed to Isaiah of Jerusalem. Chapters 40–55 (Second Isaiah) date to the late Exilic period (c. 550–538 BCE), and chapters 56–66 (Third Isaiah) to the early Persian period (c. 538–500 BCE). Redaction continued into the 5th century BCE.

- Jeremiah: Core oracles from Jeremiah’s ministry in the late 7th–early 6th centuries BCE (c. 627–587 BCE). The book was likely edited during the Exile (6th century BCE) and finalized in the Persian period, incorporating prose narratives and later additions.

- Ezekiel: Primarily from Ezekiel’s prophetic activity during the Exile (c. 593–571 BCE). The book’s final form, with its priestly and visionary content, was likely completed shortly after, c. 550 BCE.

- Hosea: Oracles from Hosea’s ministry in the Northern Kingdom (c. 750–725 BCE), with possible redaction in Judah during or after the fall of Israel (722 BCE). Final form likely 7th–6th centuries BCE.

- Joel: Difficult to date precisely due to lack of historical markers. Likely post-Exilic (5th–4th centuries BCE), though some argue for a pre-Exilic core (8th–7th centuries BCE). Its apocalyptic tone suggests a later composition.

- Amos: Oracles from Amos’ ministry in the Northern Kingdom (c. 760–750 BCE), with possible Judahite redaction after 722 BCE. Final form likely 7th–6th centuries BCE.

- Obadiah: Likely post-Exilic (5th century BCE), addressing Edom’s role in Judah’s fall (587 BCE). Some suggest an earlier core (7th–6th centuries BCE).

- Jonah: Likely a post-Exilic composition (5th–4th centuries BCE) due to its narrative style and universalist themes. Some argue for a 6th-century BCE origin, but its fictional nature suggests a later date.

- Micah: Oracles from Micah’s ministry (c. 740–700 BCE), with possible Exilic or post-Exilic additions (6th–5th centuries BCE). Final form likely 5th century BCE.

- Nahum: Oracles concerning Nineveh’s fall (612 BCE), likely composed shortly after, c. 612–600 BCE, with possible later redaction.

- Habakkuk: Oracles from the late 7th century BCE (c. 605–598 BCE), addressing Babylon’s rise. Final form likely early 6th century BCE.

- Zephaniah: Oracles from Zephaniah’s ministry (c. 640–622 BCE), with possible Exilic redaction. Final form likely 6th–5th centuries BCE.

- Haggai: Dated precisely to 520 BCE, based on internal references to the second year of Darius I. Minimal redaction, likely finalized shortly after.

- Zechariah: Chapters 1–8 from Zechariah’s ministry (c. 520–518 BCE). Chapters 9–14 (Second Zechariah) are likely later, from the 5th–4th centuries BCE, due to distinct style and historical context.

- Malachi: Post-Exilic, likely 5th century BCE (c. 450–400 BCE), addressing temple and social issues in the Persian period.

Ketuvim (Writings)

The Ketuvim include diverse genres (wisdom, poetry, history), with composition spanning a wide range. Many reached their final form in the Persian or Hellenistic periods.

- Psalms: A collection spanning centuries, with individual psalms potentially from the 10th century BCE (Davidic period) to the 5th century BCE. The collection was likely finalized in the Persian period (5th–4th centuries BCE).

- Proverbs: Contains older sayings (some possibly from Solomon’s time, 10th century BCE), but the collection was likely compiled in the Hellenistic period (c. 332–198 BCE), with final redaction in the 3rd century BCE.

- Job: Likely composed in the 6th century BCE, post-Exile, though its poetic core may reflect earlier traditions (7th–6th centuries BCE). Its philosophical tone suggests a post-Exilic context.

- Song of Songs: Possibly rooted in earlier love poetry (8th–7th centuries BCE), but likely compiled in the Persian or Hellenistic period (5th–3rd centuries BCE).

- Ruth: Likely post-Exilic (5th–4th centuries BCE), reflecting Persian-period concerns about identity and inclusion. Some argue for an earlier monarchic setting (8th–7th centuries BCE).

- Lamentations: Likely composed shortly after Jerusalem’s fall (587 BCE), with final form in the early 6th century BCE. Its poetic structure suggests rapid composition.

- Ecclesiastes: Likely composed in the Hellenistic period (c. 3rd century BCE, possibly 250–200 BCE), due to its philosophical tone and linguistic features. Some suggest a 4th-century BCE origin.

- Esther: Post-Exilic, likely 5th–4th centuries BCE, reflecting events in the Persian court. Its narrative style suggests a later date, possibly 4th century BCE.

- Daniel: Chapters 1–6 likely from the 6th century BCE (Exilic), but chapters 7–12, with apocalyptic visions, date to the 2nd century BCE (c. 167–164 BCE), during the Maccabean revolt. Final form c. 164 BCE.

- Ezra: Likely compiled in the Persian period (5th century BCE, c. 450–400 BCE), with sources from the return from Exile (538 BCE onward).

- Nehemiah: Companion to Ezra, compiled c. 450–400 BCE, with memoir material from Nehemiah’s governorship (c. 445 BCE).

- 1 Chronicles: Likely 4th century BCE, post-Exilic, retelling Israel’s history with a focus on Davidic lineage and temple worship. Draws on earlier sources (e.g., Samuel, Kings) from the 10th–6th centuries BCE.

- 2 Chronicles: Companion to 1 Chronicles, also 4th century BCE, with similar sources and theological focus on Judah’s temple and monarchy.

Notes on Scholarship and Evidence

- Earliest Evidence: The Dead Sea Scrolls (c. 2nd century BCE) provide the oldest surviving Hebrew manuscripts, confirming that many books were in near-final form by then. Earlier inscriptions, like the Khirbet Qeiyafa ostracon (c. 1000 BCE), suggest Hebrew writing existed by the early monarchy, supporting the possibility of early written traditions.

- Challenges: Dating relies on internal evidence (historical references, linguistic features) and external evidence (archaeology, ancient Near Eastern texts). The Documentary Hypothesis, though less dominant, informs Pentateuchal studies, while the Deuteronomistic History model shapes understanding of Joshua–Kings.

- Debates: Conservative scholars (e.g., Edwin R. Thiele) argue for earlier dates, especially for Pentateuchal traditions (15th–13th centuries BCE), citing Mosaic influence. Critical scholars (e.g., John J. Collins, Israel Finkelstein) favor later dates, emphasizing Exilic and post-Exilic redaction. Archaeological evidence, like the Ketef Hinnom scroll (7th century BCE), supports pre-Exilic writing but not necessarily full texts.

- Compilation Over Time: Most books evolved through oral traditions, written sources, and multiple redactions. For example, the Pentateuch’s final form reflects post-Exilic priorities, but earlier traditions may date back centuries. Prophetic books often combine a prophet’s oracles with later editorial framing.

***

📜 The Torah / Pentateuch (Genesis – Deuteronomy)

Traditional attribution: Moses

Scholarly view: A compilation of sources over centuries

| Book | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Genesis | 10th–5th century BCE | Contains material from the J (Yahwist, ~950 BCE), E (Elohist, ~850 BCE), P (Priestly, ~6th century BCE), and D (Deuteronomist, ~7th century BCE) sources. Final form likely post-exilic (5th century BCE). |

| Exodus | Same as Genesis | Composite from J, E, P, and D traditions. |

| Leviticus | ca. 6th–5th century BCE | Primarily Priestly material, likely written or compiled during the Babylonian Exile. |

| Numbers | 10th–5th century BCE | Composite like Genesis and Exodus. Final form post-exilic. |

| Deuteronomy | ca. 7th century BCE, with later edits | Core written during Josiah’s reforms (~620 BCE). Final form edited in exile or post-exile. |

📘 Historical Books (Joshua – Esther)

| Book | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Joshua | 7th–6th century BCE | Possibly Deuteronomistic History; post-Josiah, edited in exile. |

| Judges | 7th–6th century BCE | Part of the Deuteronomistic History (DtrH). |

| 1 & 2 Samuel | 7th–6th century BCE | Earlier sources from 10th–9th c. BCE; edited by Deuteronomistic historians. |

| 1 & 2 Kings | 6th century BCE | Finalized during Babylonian Exile; strong Deuteronomistic theology. |

| Ruth | 5th–4th century BCE | Set in Judges era, but written later; some see it as a response to Ezra-Nehemiah’s exclusionary policies. |

| 1 & 2 Chronicles | ca. 400–350 BCE | Post-exilic; retelling of Samuel–Kings from a priestly perspective. |

| Ezra–Nehemiah | ca. 400–350 BCE (some argue slightly later) | Compiled from earlier memoirs and edited in post-exilic period. |

| Esther | 4th–3rd century BCE | Possibly fictional court tale with Persian setting; no direct mention of God. |

🎙️ Wisdom and Poetry (Job – Song of Songs)

| Book | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Job | Core: 6th–5th century BCE; edits later | Possibly written in exile; explores innocent suffering. |

| Psalms | ca. 10th–3rd century BCE | Collected over centuries; some psalms trace to Davidic era, others are post-exilic. |

| Proverbs | Core: 10th–6th century BCE; final: ~4th c. | Some sayings may be Solomonic; final compilation likely late Persian period. |

| Ecclesiastes | ca. 3rd century BCE | Philosophical reflections, traditionally attributed to Solomon. |

| Song of Songs | ca. 4th–3rd century BCE | Love poetry; possibly allegorical or secular; final form Hellenistic. |

| Lamentations | ca. 586–500 BCE | Likely written after the destruction of Jerusalem by Babylon. |

📢 Major Prophets (Isaiah – Daniel)

| Book | Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Isaiah | Parts from 8th–5th century BCE | Divided into First Isaiah (1–39) ~740–700 BCE, Second Isaiah (40–55) ~540 BCE (exilic), Third Isaiah (56–66) ~500–450 BCE (post-exilic). |

| Jeremiah | 7th–6th century BCE | Contains autobiographical materials, later edited. |

| Ezekiel | ca. 593–571 BCE | Written during exile in Babylon. |

| Daniel | ca. 167–164 BCE | Set in Babylon, but written during Antiochus IV’s persecution; earliest example of apocalyptic literature in Bible. |

📣 Minor Prophets (The Twelve)

Often collected as one book in the Hebrew Bible. Dates vary per prophet:

| Book | Date |

|---|---|

| Hosea | 8th century BCE (before 722 BCE) |

| Joel | ca. 500–350 BCE (disputed: some say earlier) |

| Amos | ca. 760–750 BCE |

| Obadiah | ca. 6th century BCE |

| Jonah | ca. 4th–3rd century BCE |

| Micah | ca. 740–700 BCE |

| Nahum | ca. 620–610 BCE |

| Habakkuk | ca. 610–597 BCE |

| Zephaniah | ca. 640–609 BCE |

| Haggai | 520 BCE |

| Zechariah | Chapters 1–8: 520–518 BCE; 9–14: ~4th century |

| Malachi | ca. 450–400 BCE |

***

Based on the latest scholarly consensus, here’s a comprehensive list of when each Old Testament book is thought to have been written:

Torah (Five Books of Moses)

Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy

- The majority of modern biblical scholars believe that the Torah reached its present form in the post-exilic period (5th century BCE)

- However, these books contain material from various periods, with some traditions potentially dating much earlier

Historical Books

Joshua, Judges, 1-2 Samuel, 1-2 Kings

- This group of books, plus Deuteronomy, is called the “Deuteronomistic history” by scholars, appearing in two “editions”, the first in the reign of Judah’s King Josiah (late 7th century BCE), the second during the exile (6th century BCE)

- Final form: 6th century BCE (Babylonian exile period)

1-2 Chronicles

- Chronicles was composed between 400 and 250 BCE, probably in the period 350–300 BCE

Ezra-Nehemiah

- Ezra–Nehemiah may have reached its final form as late as the Ptolemaic period, c. 300–200 BCE

Ruth

- The Book of Ruth is commonly dated to the Persian period (538-332 BCE)

Esther

- Esther to the 3rd or 4th centuries BCE

Poetic/Wisdom Literature

Job

- It is generally agreed that Job comes from between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE

Psalms

- The psalms making up the first two-thirds of the psalter are predominantly pre-exilic and the last third predominantly post-exilic. The collected book of Psalms was possibly given its modern shape and division into five parts in the post-exilic period, although it continued to be revised and expanded well into Hellenistic and even Roman times

Proverbs

- Proverbs is a “collection of collections” relating to a pattern of life which lasted for more than a millennium, and impossible to date

- Contains material from various periods, making precise dating difficult

Ecclesiastes

- Ecclesiastes can be no earlier than about 450 BCE, due to the presence of Persian loan-words and Aramaic idioms, and no later than 180 BCE

Song of Songs

- The Song of Songs could have been composed at any time after the 6th century BCE

Lamentations

- It is generally accepted that the destruction of Jerusalem by Babylon in 586 BCE forms the background to the Book of Lamentations

Major Prophets

Isaiah

- Scholars recognise three “sections” in the Book of Isaiah

- First Isaiah (chapters 1-39): 8th century BCE

- Second Isaiah (chapters 40-55): 6th century BCE (exile period)

- Third Isaiah (chapters 56-66): 5th century BCE (post-exilic)

Jeremiah

- The Greek version was probably finalised in the early Persian period and translated into Greek in the 3rd century BCE, and the Hebrew version dates from some point between then and the 2nd century BCE

Ezekiel

- Internal evidence dates the visions to between 593 and 571 BCE. While the book probably reflects much of the historic Ezekiel, it is the product of a long and complex history, with significant additions by a “school” of later followers

Daniel

- The Book of Daniel can be dated more precisely to 164 BCE thanks to its veiled prophecy of the death of a Greek king of Syria

Minor Prophets

In the Hebrew Bible the Twelve Minor Prophets are a single collection edited in the Second Temple period, but the collection is broken up in Christian Bibles. With the exception of Jonah, which scholars regard as fictional, there exists an original core of prophetic tradition behind each book

The individual books span from the 8th century BCE (Amos, Hosea) to the post-exilic period (Haggai, Zechariah, Malachi).

Key Points:

- Much of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament may have been assembled in the 5th century BCE

- Many books underwent complex editorial processes over centuries

- Dating relies primarily on internal evidence and historical references

- The final canonical form of most books was established during or after the Babylonian exile (6th-5th centuries BCE)

This represents the current scholarly consensus, though individual scholars may hold different views on specific books, and new archaeological discoveries continue to refine our understanding of biblical composition dates.

***