The following is an AI generated essay. However, the ideas influencing the essay are my own. To save time I will often use AI to compress my ideas into essay form, which I can then refer to later. In my opinion that is one of the ways to correctly use AI. And this blog is as good a place as any to post it.

Paul, Israel, Adam, and the Nations

A Second Temple Jewish Logic of Election, Atonement, and New Creation

Introduction

The apostle Paul is often portrayed as the architect of a new, universal religion that abandoned Israel’s particular story in favor of a generalized theology of salvation. Historically, this portrayal is misleading. Paul understood himself not as departing from Israel’s scriptures, but as re-reading them under the pressure of a single, destabilizing event: the resurrection of Jesus.

This essay argues that Paul’s theology is best understood as a carefully balanced synthesis of three narrative layers already present in Second Temple Judaism:

- Creation (Adam and humanity)

- Covenant (Israel and Torah)

- Eschatology (Messiah and resurrection)

Paul’s inclusion of Gentiles does not bypass Israel, nor does it flatten Jewish categories into abstraction. Instead, it follows a coherent internal logic in which Israel remains central, Adam explains humanity’s universal plight, and Jesus stands at the intersection of both stories.

1. Temple Judaism and the Limits of Atonement

In the First and Second Temple periods, Israelites did not believe their sacrifices directly atoned for the sins of the nations. Temple sacrifice was:

- Covenantal (for Israel)

- Geographically and cultically located (land, sanctuary, priesthood)

- Purificatory, especially for Israel’s sin and the sanctuary polluted by it

Gentiles could offer sacrifices, and the Temple was seen as the cosmic center sustaining order for the whole world, but this benefit was indirect. The nations were not cleansed of sin simply because Israel offered sacrifice.

This distinction is crucial. Later Christian claims of universal atonement represent a genuine theological shift, not a straightforward continuation of Temple belief.

2. Paul’s Scriptural Justification: Not Innovation, but Re-reading

Paul knew his claims were radical. He therefore grounded them explicitly in Israel’s scriptures.

Abraham before Torah

Paul emphasizes that Abraham was declared righteous before circumcision and before the Law (Genesis 15:6). This allowed Paul to argue that:

- Covenant faithfulness could precede Torah

- Gentile inclusion was not an afterthought, but anticipated from the beginning

Deuteronomy’s Curse Logic

Paul reads Deuteronomy’s warnings seriously. Israel’s failure under Torah places her under covenant curse (exile). Jesus’ crucifixion—“hanging on a tree”—forces a re-reading of Deuteronomy 21:23. For Paul:

- The Messiah bears the curse on behalf of Israel

- The Law is not evil; sin exploits it

- The curse must be lifted before Abraham’s blessing can flow outward

Resurrection as the Turning Point

Paul’s theology does not pivot on Jesus’ death alone, but on resurrection. Resurrection signals:

- The beginning of the age to come

- The defeat of death

- The vindication of Jesus as Messiah

Without resurrection, Paul explicitly says his gospel collapses.

3. Why Gentiles Needed Justification

Gentiles were not under the Mosaic Law. So why, according to Paul, did they need salvation?

The Adamic Problem (Romans 5)

Paul’s answer is Adam.

- Sin and death enter the world through Adam

- Death reigns over all humanity before the Law

- The Law intensifies sin but does not create it

This allows Paul to distinguish:

- Israel’s problem: covenantal failure under Torah

- Humanity’s problem: enslavement to sin and death through Adam

Gentiles are condemned not as Torah-breakers, but as creatures who have misused creation and fallen under the power of death.

4. Adam and Israel: Parallel Stories

Second Temple Jews already recognized parallels between Adam and Israel:

| Adam | Israel |

|---|---|

| Placed in Eden | Placed in the land |

| Given a command | Given Torah |

| Warned of death | Warned of exile |

| Exiled eastward | Exiled among nations |

Paul does not reduce Adam to Israel, nor Israel to Adam. Instead:

- Adam is the prototype

- Israel is the recapitulation

- Christ is the resolution of both

Jesus succeeds where both Adam and Israel fail—not by abandoning Israel’s story, but by embodying it faithfully.

5. Two Problems, One Messiah

Paul’s theology can be summarized as addressing two distinct curses:

- The curse of the Law (Israel’s covenantal failure)

- The curse of Adam (humanity’s enslavement to death)

Jesus’ death and resurrection deal with both, but not in the same way.

- As Israel’s Messiah, Jesus bears the Law’s curse

- As representative human, Jesus undoes Adam’s reign of death

The order matters: Adam is resolved through Israel’s Messiah.

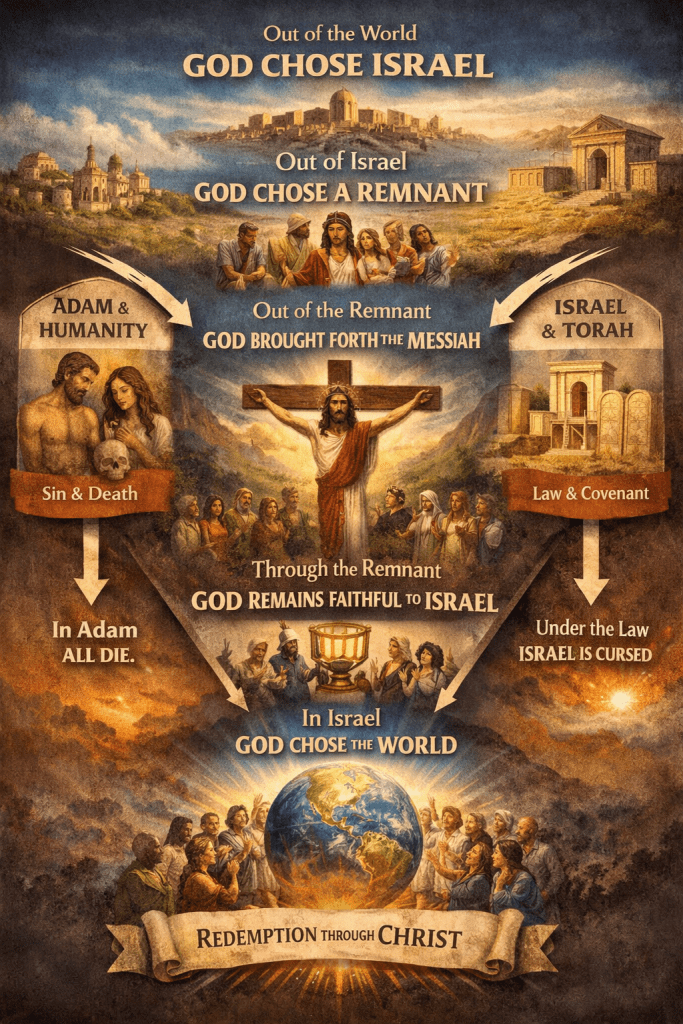

6. Paul’s Chiasmic Logic of Election

Paul’s theology of election can be expressed as a dynamic narrowing and widening:

Out of the world God chose Israel

…Out of Israel God chose a remnant

……Out of the remnant God brought forth the Messiah

……In the Messiah God formed a faithful remnant

…Through this remnant God remains faithful to Israel

In Israel God brings blessing to the world

This structure preserves:

- Israel’s priority

- Gentile inclusion

- The Messiah as the hinge of history

- Election as vocation, not favoritism

Paul explicitly rejects the idea that the remnant replaces Israel. Instead, the remnant is the means by which God remains faithful to Israel, and Israel is the means by which God blesses the nations.

7. Where Later Christianity Breaks with Paul

Paul’s logic often breaks down in later Christianity due to simplification:

Adam Absorbs Everything

Adam becomes the sole explanatory category, while Israel’s covenantal role fades. This flattens Paul’s careful distinction between creation-failure and covenant-failure.

The Law Becomes the Villain

Torah is reinterpreted as legalism rather than gift. This distorts Paul’s claim that the Law is “holy and good.”

Resurrection Loses Centrality

Atonement becomes focused almost entirely on the cross as payment for guilt, rather than resurrection as the defeat of death and the beginning of new creation.

Israel Is Explained Away

Romans 9–11 is sidelined. The church becomes the endpoint rather than the participant in an unfinished story.

These shifts were historically understandable—especially in a Gentile-majority, post-Temple world—but they are not faithful to Paul’s own architecture.

Conclusion

Paul did not abandon Israel, mythologize Adam away, or invent a new religion detached from Jewish scripture. He was a Second Temple Jew who believed that God had acted decisively within Israel’s story to resolve a problem that reached back to Adam and outward to the nations.

For Paul:

- Israel remains chosen

- Adam explains universal need

- Christ stands at the center

- Resurrection signals new creation

- History is still unfolding

Gentile inclusion is not a detour from Israel’s vocation—it is the goal toward which that vocation always pointed.

Understanding Paul this way does not require agreeing with him. But it does require taking him seriously on his own terms.

***

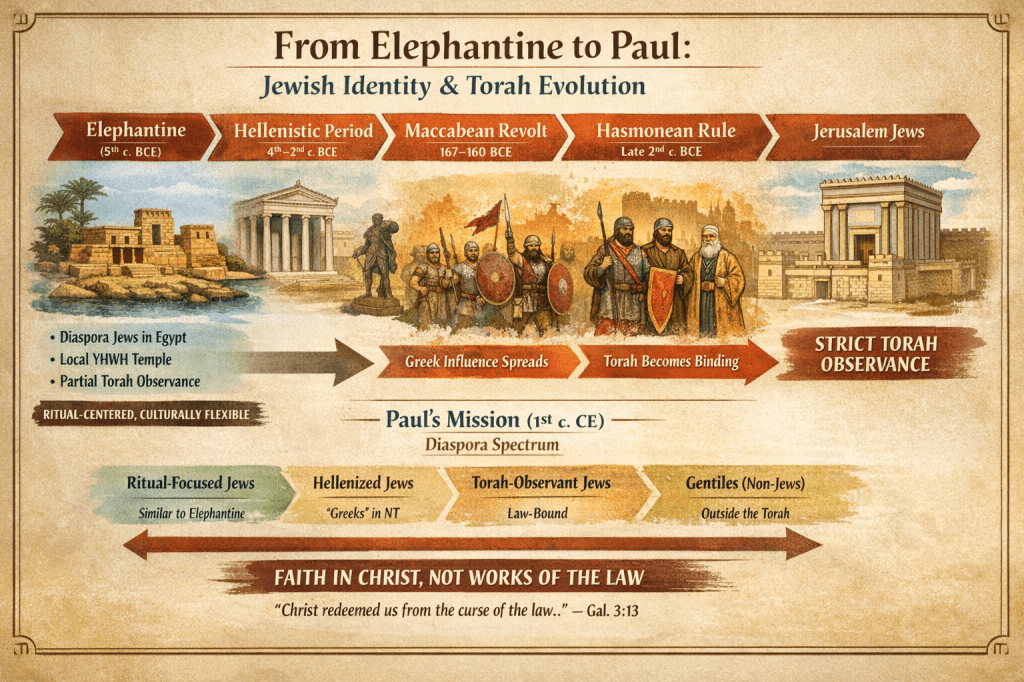

From Elephantine to Galatia: Understanding Diaspora Judaism and Paul’s Mission

The history of Jewish communities outside Jerusalem reveals a rich diversity of religious practice long before Torah law became universally binding. One of the clearest examples is the Jewish community at Elephantine, a military colony in southern Egypt during the 5th century BCE. Studying Elephantine not only illuminates early diaspora Judaism but also helps us understand the audiences that Paul encountered on his missionary journeys centuries later.

1. The Elephantine Community

Elephantine was a Judahite military colony, stationed on Egypt’s southern frontier before the Persian conquest (c. 525 BCE). Its members were likely Judean soldiers or mercenaries who migrated to Egypt before the major Deuteronomic reforms of the late 7th century BCE. Consequently, their religious practice reflects a pre-exilic, ritual-focused Yahwism:

- They had their own temple devoted to YHWH, where priests oversaw sacrifices.

- Their daily life and legal documents show partial adherence to Torah traditions, but not full Torah law enforcement.

- They interacted with local Egyptians and other peoples, suggesting a degree of cultural flexibility and syncretism.

- Notably, their petitions to the Jerusalem priesthood for temple support did not receive clear approval, showing the limits of central authority at the time.

In short, Elephantine Jews were religiously Jewish but socially flexible, practicing a form of Judaism that was ritual-centered rather than text-centered.

2. Why Elephantine Was Eventually Forgotten

By the 2nd century BCE, Judaism had begun a process of centralization and textualization that made communities like Elephantine historically obsolete:

- Centralization of worship in Jerusalem made autonomous temples theologically problematic.

- Torah law became the definitive marker of Jewish identity, replacing older ritual customs.

- Diaspora communities like Elephantine lacked scribal and institutional power, meaning their traditions were not preserved.

- As Jerusalem-centered Judaism solidified, communities outside its influence were quietly ignored or absorbed, leading Elephantine to fade from memory.

Elephantine, therefore, provides a snapshot of Judaism before Torah law became normative, illustrating how Jewish identity and practice evolved over centuries.

3. The Emergence of Normative Torah

The transformation from Elephantine-style Judaism to Torah-centered Judaism was largely complete by the 2nd century BCE, driven by historical pressures:

- Hellenistic Rule and Seleucid Oppression: Greek culture and political control threatened Jewish religious practices, culminating in Antiochus IV’s desecration of the Jerusalem Temple.

- Priestly Corruption and Internal Crisis: Disputes over legitimate leadership and proper observance highlighted the need for a standardized legal framework.

- The Maccabean Revolt (167–160 BCE) established Hasmonean rule, making Torah observance state-enforced, not optional.

- Diaspora Pressures: Torah law became a marker of identity, distinguishing Jews from surrounding Gentiles.

The result: Torah became binding and normative, defining Jewish identity for the first time in a widespread, enforceable way.

4. Diaspora Jews in Paul’s Time

By the 1st century CE, diaspora Jewish communities still exhibited considerable diversity in Torah observance and cultural assimilation:

- Elephantine-type Jews: Highly ritual-centered, partially Torah-observant, integrated into local culture.

- Hellenized diaspora Jews (“Greeks” in the NT sense): Some Torah knowledge, varying observance, Greek names and customs, partially assimilated.

- Jerusalem-centered Jews: Fully Torah-observant, resistant to Hellenistic influence, centralized around Temple and priesthood.

- Gentiles: Non-Jews with no obligation under Torah, often converts to Judaism via proselytism.

This spectrum helps us understand Paul’s ministry: many Jews outside Jerusalem were culturally and religiously flexible, making them receptive to his message of faith in Christ over strict law observance.

5. Paul and the Galatian Audience

In Galatians 3:13, Paul writes:

“Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us…”

Here, he addresses an audience that includes diaspora Jews and Gentile converts who were under pressure from “Judaizers” to adopt Torah practices like circumcision. These Jews:

- Likely resembled Elephantine-type or Hellenized diaspora Jews, partially observant but culturally integrated.

- Faced choices between ritual identity and faith in Christ.

- Needed reassurance that salvation did not require full Torah compliance, particularly circumcision, the visible marker of law.

Paul’s argument is historically consistent: he appeals to the flexible, diaspora identity that existed in Jewish communities long before Torah law was universally enforced.

6. Conclusion

The Elephantine community shows us that early Jewish diaspora life was diverse and adaptable. Ritual practice, local temple worship, and flexible law observance were the norm outside Jerusalem. Over centuries, historical pressures—imperial rule, Hellenization, and the Hasmonean consolidation—made Torah law binding and central to Jewish identity. By Paul’s time, many diaspora Jews still embodied the Elephantine-type flexibility, explaining why his gospel could resonate with Jews and Gentiles who were devout but not fully Torah-bound.

Understanding this continuum—from Elephantine to Galatia—illuminates both the historical development of Judaism and the social context of Paul’s missionary work, highlighting how faith and law interacted in a changing world.

***