There is No Santa

Imagine a young boy who believes in Santa Claus. He believes that the presents he finds under the tree each Christmas morning were placed there by a magical man who came down the chimney, and who afterward hopped on his sleigh pulled by flying reindeer.

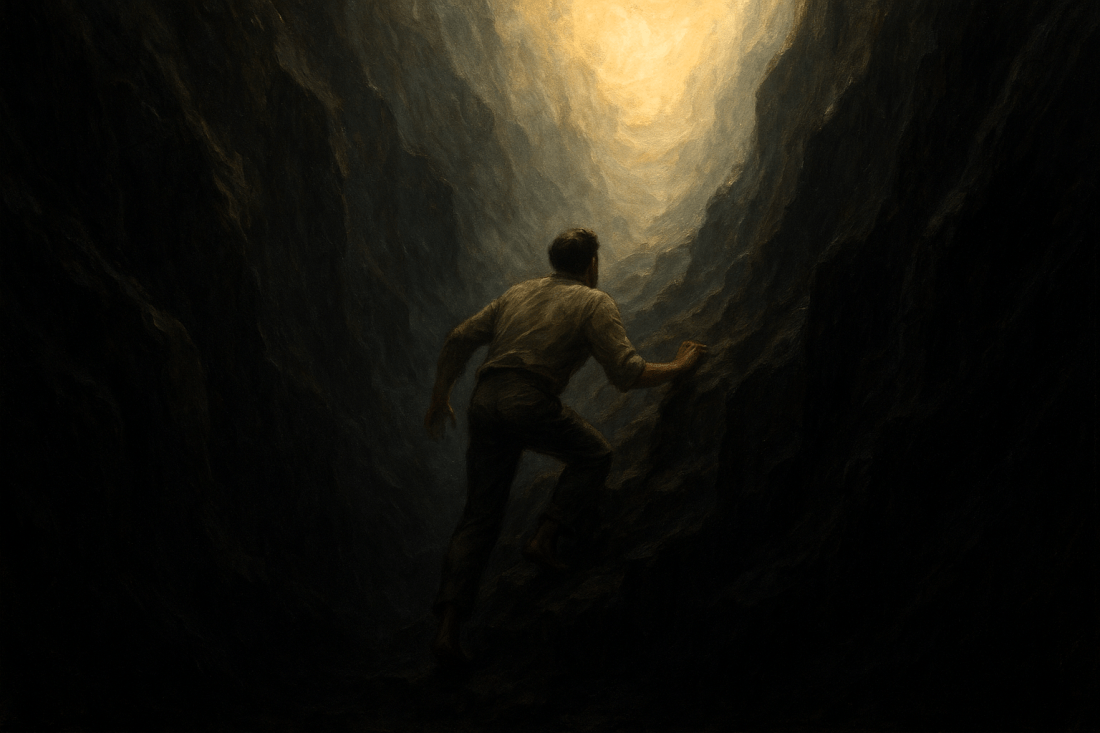

But, one Christmas Eve, the boy decides he wants to see Santa for real and so he sneaks out of his room late at night hoping to catch Santa in action. What he does see, however, is his own parents carefully laying out presents, one by one, around the base of the tree. And so, he knows the truth. It is in fact his own parents who are delivering the goods.

Now, with this knowledge, would it be proper for the boy to then believe that it is his own parents who slid down the chimney? And it his own parents who will fly off into the night on the sleigh? No, of course not. The boy must disregard the entire Santa narrative. There’s no one coming down the chimney. It’s all his parents buying the presents from the store, wrapping them out of sight, and placing them under the tree. Once the boy discovers the truth about one thing, he must apply that truth to everything else.

First Century Cosmology

First century Christians did not have telescopes. They believed the realm above them was a series of layers transcending the dome of the sky. They believed that angels and God literally resided in and above the layers containing the sun, moon, and stars. God’s throne room was a literal place up in what we would call “outer space.” When Jesus ascended up to the Father, to sit at His right hand, Jesus literally went up to sit on a literal throne in a literal throne room.

Since Jesus was up in outer space, of course when He returns, he will return from outer space. Where else would He come from?

21st Century Cosmology

Today we have telescopes. We know that we live in one galaxy among billions, and that each galaxy contains billions, if not trillions, of stars. The universe is so vast, it is beyond comprehension. In fact, the universe is likely infinite. We know this now.

We know that there is no Santa. Therefore, is it proper for us to continue to believe that one day the world will see Jesus descending down to the earth through the layers of the heavens as they believed He would in the 1st century? Should we combine their cosmology with our own? No, of course not. Ask any Christian today where heaven is, and unless he’s a flat-earther, he will likely say that heaven is located in the spiritual realm, someplace beyond the material realm that we do not have access to.

New Testament Eschatological Language

New Testament (NT) eschatology is primarily Israel’s eschatology. The Church’s eschatology builds upon it, but then transcends it. The cosmos coming under judgement for the NT authors was the Israelite cosmos. The end was near, at hand, at the door, soon, and about to happen. Every NT author believed he was living in the last days. And he was, to the degree that the old order of things was coming to an end. The apocalyptic language of the NT reflects this.

Israel’s eschatology is not the Church’s eschatology. The Church’s eschatology is this: Just as a dragnet draws all the fish into the boat, so is all creation being drawn to the Father by the redemptive work of Christ. We don’t know when this work will be complete, and we don’t know what it will finally look like. For now it is beyond our comprehension, beyond our reach.

It’s okay to be somewhat agnostic when it comes to eschatology. Embrace the mystery. Whatever you do, don’t go on believing that your dad has a pack of flying reindeer hidden away in a barn somewhere.

We Are Not Israel

Israel is gone. Our faith is not “Judeo/Christian.” We are just Christian. Yes, Jesus was the Messiah Israel was waiting for, but He was not the Messiah they were expecting. Jesus was not the blood soaked Davidic warrior coming to destroy Rome and establish a powerful Israelite theocracy the 1st century Jews were hoping for. This is why He was rejected.

Jesus subverted all Messianic expectations. His kingdom is not of this world. He came to conquer a higher enemy. He came to do the will of the Father, not Israel. The Father’s will is to redeem His creation. This is what Christianity is: The redemption of creation through Christ.

For Christians, Israel has become allegory. The Old Testament scriptures are transformed to types and shadows. It’s not our literal history. It’s our mythology.

Most Christians live like this even if not fully aware of it. They may say the stories are literal history, but they always apply the stories allegorically to their own life’s journey. It doesn’t matter if the stories are literal history or not; anything to do with Israel we allegorize.

Jesus is not coming down from the sky. Israelite cosmology is not true. That’s okay, because we are Christians. We know more. We’ve seen more. We know what is mythology and what is reality. We know the truth, and what we know is true; we must apply it to everything else.