This video below is worth watching. I suppose we shall see in the professor’s predictions come true in not too long a period of time.

Category: eschatology

Dale C. Allison Interview (Video)

If Evangelical Fundamentalism is the true version of Christianity then I am in trouble since I can’t bring myself to believe in it. Thankfully Christian faith is varied enough that one can find a niche to remain a believer in. There are two scholars which showed me this was possible: David Bentley Hart and Dale C. Allison. Below is recent interview done with Allison (ignore the click bait titles)…

Refining Paul’s Theology

The following is an AI generated essay. However, the ideas influencing the essay are my own. To save time I will often use AI to compress my ideas into essay form, which I can then refer to later. In my opinion that is one of the ways to correctly use AI. And this blog is as good a place as any to post it.

Paul, Israel, Adam, and the Nations

A Second Temple Jewish Logic of Election, Atonement, and New Creation

Introduction

The apostle Paul is often portrayed as the architect of a new, universal religion that abandoned Israel’s particular story in favor of a generalized theology of salvation. Historically, this portrayal is misleading. Paul understood himself not as departing from Israel’s scriptures, but as re-reading them under the pressure of a single, destabilizing event: the resurrection of Jesus.

This essay argues that Paul’s theology is best understood as a carefully balanced synthesis of three narrative layers already present in Second Temple Judaism:

- Creation (Adam and humanity)

- Covenant (Israel and Torah)

- Eschatology (Messiah and resurrection)

Paul’s inclusion of Gentiles does not bypass Israel, nor does it flatten Jewish categories into abstraction. Instead, it follows a coherent internal logic in which Israel remains central, Adam explains humanity’s universal plight, and Jesus stands at the intersection of both stories.

1. Temple Judaism and the Limits of Atonement

In the First and Second Temple periods, Israelites did not believe their sacrifices directly atoned for the sins of the nations. Temple sacrifice was:

- Covenantal (for Israel)

- Geographically and cultically located (land, sanctuary, priesthood)

- Purificatory, especially for Israel’s sin and the sanctuary polluted by it

Gentiles could offer sacrifices, and the Temple was seen as the cosmic center sustaining order for the whole world, but this benefit was indirect. The nations were not cleansed of sin simply because Israel offered sacrifice.

This distinction is crucial. Later Christian claims of universal atonement represent a genuine theological shift, not a straightforward continuation of Temple belief.

2. Paul’s Scriptural Justification: Not Innovation, but Re-reading

Paul knew his claims were radical. He therefore grounded them explicitly in Israel’s scriptures.

Abraham before Torah

Paul emphasizes that Abraham was declared righteous before circumcision and before the Law (Genesis 15:6). This allowed Paul to argue that:

- Covenant faithfulness could precede Torah

- Gentile inclusion was not an afterthought, but anticipated from the beginning

Deuteronomy’s Curse Logic

Paul reads Deuteronomy’s warnings seriously. Israel’s failure under Torah places her under covenant curse (exile). Jesus’ crucifixion—“hanging on a tree”—forces a re-reading of Deuteronomy 21:23. For Paul:

- The Messiah bears the curse on behalf of Israel

- The Law is not evil; sin exploits it

- The curse must be lifted before Abraham’s blessing can flow outward

Resurrection as the Turning Point

Paul’s theology does not pivot on Jesus’ death alone, but on resurrection. Resurrection signals:

- The beginning of the age to come

- The defeat of death

- The vindication of Jesus as Messiah

Without resurrection, Paul explicitly says his gospel collapses.

3. Why Gentiles Needed Justification

Gentiles were not under the Mosaic Law. So why, according to Paul, did they need salvation?

The Adamic Problem (Romans 5)

Paul’s answer is Adam.

- Sin and death enter the world through Adam

- Death reigns over all humanity before the Law

- The Law intensifies sin but does not create it

This allows Paul to distinguish:

- Israel’s problem: covenantal failure under Torah

- Humanity’s problem: enslavement to sin and death through Adam

Gentiles are condemned not as Torah-breakers, but as creatures who have misused creation and fallen under the power of death.

4. Adam and Israel: Parallel Stories

Second Temple Jews already recognized parallels between Adam and Israel:

| Adam | Israel |

|---|---|

| Placed in Eden | Placed in the land |

| Given a command | Given Torah |

| Warned of death | Warned of exile |

| Exiled eastward | Exiled among nations |

Paul does not reduce Adam to Israel, nor Israel to Adam. Instead:

- Adam is the prototype

- Israel is the recapitulation

- Christ is the resolution of both

Jesus succeeds where both Adam and Israel fail—not by abandoning Israel’s story, but by embodying it faithfully.

5. Two Problems, One Messiah

Paul’s theology can be summarized as addressing two distinct curses:

- The curse of the Law (Israel’s covenantal failure)

- The curse of Adam (humanity’s enslavement to death)

Jesus’ death and resurrection deal with both, but not in the same way.

- As Israel’s Messiah, Jesus bears the Law’s curse

- As representative human, Jesus undoes Adam’s reign of death

The order matters: Adam is resolved through Israel’s Messiah.

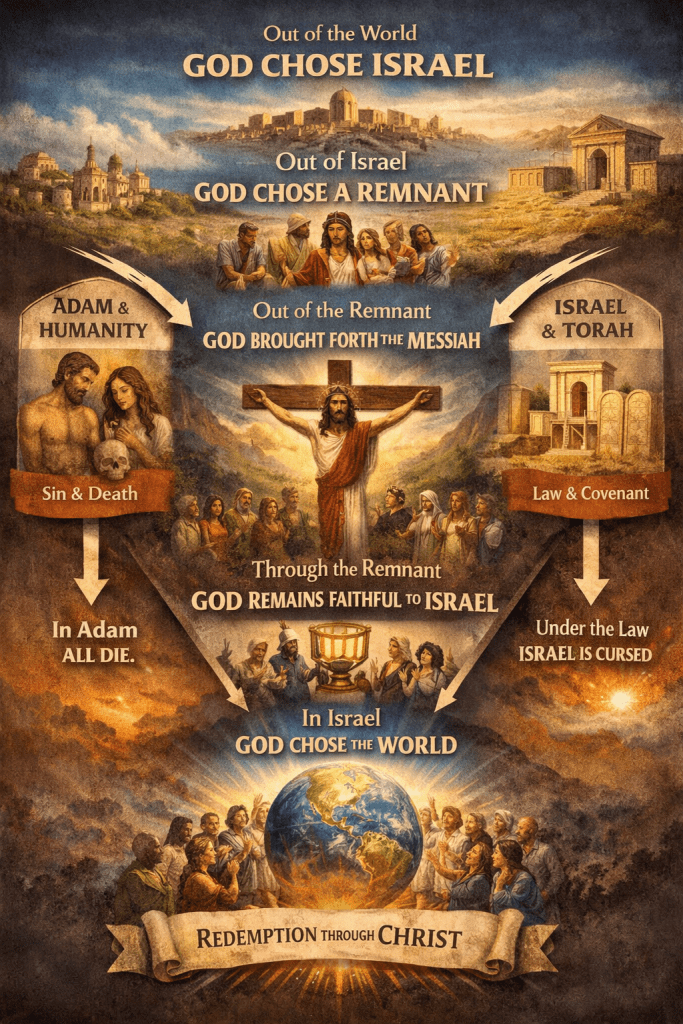

6. Paul’s Chiasmic Logic of Election

Paul’s theology of election can be expressed as a dynamic narrowing and widening:

Out of the world God chose Israel

…Out of Israel God chose a remnant

……Out of the remnant God brought forth the Messiah

……In the Messiah God formed a faithful remnant

…Through this remnant God remains faithful to Israel

In Israel God brings blessing to the world

This structure preserves:

- Israel’s priority

- Gentile inclusion

- The Messiah as the hinge of history

- Election as vocation, not favoritism

Paul explicitly rejects the idea that the remnant replaces Israel. Instead, the remnant is the means by which God remains faithful to Israel, and Israel is the means by which God blesses the nations.

7. Where Later Christianity Breaks with Paul

Paul’s logic often breaks down in later Christianity due to simplification:

Adam Absorbs Everything

Adam becomes the sole explanatory category, while Israel’s covenantal role fades. This flattens Paul’s careful distinction between creation-failure and covenant-failure.

The Law Becomes the Villain

Torah is reinterpreted as legalism rather than gift. This distorts Paul’s claim that the Law is “holy and good.”

Resurrection Loses Centrality

Atonement becomes focused almost entirely on the cross as payment for guilt, rather than resurrection as the defeat of death and the beginning of new creation.

Israel Is Explained Away

Romans 9–11 is sidelined. The church becomes the endpoint rather than the participant in an unfinished story.

These shifts were historically understandable—especially in a Gentile-majority, post-Temple world—but they are not faithful to Paul’s own architecture.

Conclusion

Paul did not abandon Israel, mythologize Adam away, or invent a new religion detached from Jewish scripture. He was a Second Temple Jew who believed that God had acted decisively within Israel’s story to resolve a problem that reached back to Adam and outward to the nations.

For Paul:

- Israel remains chosen

- Adam explains universal need

- Christ stands at the center

- Resurrection signals new creation

- History is still unfolding

Gentile inclusion is not a detour from Israel’s vocation—it is the goal toward which that vocation always pointed.

Understanding Paul this way does not require agreeing with him. But it does require taking him seriously on his own terms.

***

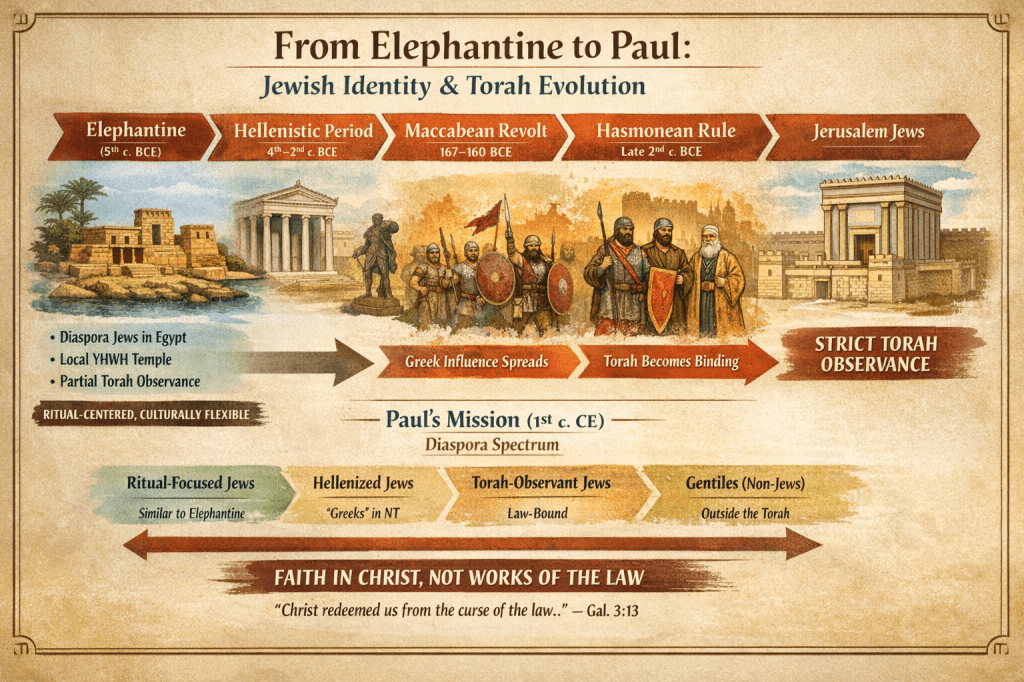

From Elephantine to Galatia: Understanding Diaspora Judaism and Paul’s Mission

The history of Jewish communities outside Jerusalem reveals a rich diversity of religious practice long before Torah law became universally binding. One of the clearest examples is the Jewish community at Elephantine, a military colony in southern Egypt during the 5th century BCE. Studying Elephantine not only illuminates early diaspora Judaism but also helps us understand the audiences that Paul encountered on his missionary journeys centuries later.

1. The Elephantine Community

Elephantine was a Judahite military colony, stationed on Egypt’s southern frontier before the Persian conquest (c. 525 BCE). Its members were likely Judean soldiers or mercenaries who migrated to Egypt before the major Deuteronomic reforms of the late 7th century BCE. Consequently, their religious practice reflects a pre-exilic, ritual-focused Yahwism:

- They had their own temple devoted to YHWH, where priests oversaw sacrifices.

- Their daily life and legal documents show partial adherence to Torah traditions, but not full Torah law enforcement.

- They interacted with local Egyptians and other peoples, suggesting a degree of cultural flexibility and syncretism.

- Notably, their petitions to the Jerusalem priesthood for temple support did not receive clear approval, showing the limits of central authority at the time.

In short, Elephantine Jews were religiously Jewish but socially flexible, practicing a form of Judaism that was ritual-centered rather than text-centered.

2. Why Elephantine Was Eventually Forgotten

By the 2nd century BCE, Judaism had begun a process of centralization and textualization that made communities like Elephantine historically obsolete:

- Centralization of worship in Jerusalem made autonomous temples theologically problematic.

- Torah law became the definitive marker of Jewish identity, replacing older ritual customs.

- Diaspora communities like Elephantine lacked scribal and institutional power, meaning their traditions were not preserved.

- As Jerusalem-centered Judaism solidified, communities outside its influence were quietly ignored or absorbed, leading Elephantine to fade from memory.

Elephantine, therefore, provides a snapshot of Judaism before Torah law became normative, illustrating how Jewish identity and practice evolved over centuries.

3. The Emergence of Normative Torah

The transformation from Elephantine-style Judaism to Torah-centered Judaism was largely complete by the 2nd century BCE, driven by historical pressures:

- Hellenistic Rule and Seleucid Oppression: Greek culture and political control threatened Jewish religious practices, culminating in Antiochus IV’s desecration of the Jerusalem Temple.

- Priestly Corruption and Internal Crisis: Disputes over legitimate leadership and proper observance highlighted the need for a standardized legal framework.

- The Maccabean Revolt (167–160 BCE) established Hasmonean rule, making Torah observance state-enforced, not optional.

- Diaspora Pressures: Torah law became a marker of identity, distinguishing Jews from surrounding Gentiles.

The result: Torah became binding and normative, defining Jewish identity for the first time in a widespread, enforceable way.

4. Diaspora Jews in Paul’s Time

By the 1st century CE, diaspora Jewish communities still exhibited considerable diversity in Torah observance and cultural assimilation:

- Elephantine-type Jews: Highly ritual-centered, partially Torah-observant, integrated into local culture.

- Hellenized diaspora Jews (“Greeks” in the NT sense): Some Torah knowledge, varying observance, Greek names and customs, partially assimilated.

- Jerusalem-centered Jews: Fully Torah-observant, resistant to Hellenistic influence, centralized around Temple and priesthood.

- Gentiles: Non-Jews with no obligation under Torah, often converts to Judaism via proselytism.

This spectrum helps us understand Paul’s ministry: many Jews outside Jerusalem were culturally and religiously flexible, making them receptive to his message of faith in Christ over strict law observance.

5. Paul and the Galatian Audience

In Galatians 3:13, Paul writes:

“Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us…”

Here, he addresses an audience that includes diaspora Jews and Gentile converts who were under pressure from “Judaizers” to adopt Torah practices like circumcision. These Jews:

- Likely resembled Elephantine-type or Hellenized diaspora Jews, partially observant but culturally integrated.

- Faced choices between ritual identity and faith in Christ.

- Needed reassurance that salvation did not require full Torah compliance, particularly circumcision, the visible marker of law.

Paul’s argument is historically consistent: he appeals to the flexible, diaspora identity that existed in Jewish communities long before Torah law was universally enforced.

6. Conclusion

The Elephantine community shows us that early Jewish diaspora life was diverse and adaptable. Ritual practice, local temple worship, and flexible law observance were the norm outside Jerusalem. Over centuries, historical pressures—imperial rule, Hellenization, and the Hasmonean consolidation—made Torah law binding and central to Jewish identity. By Paul’s time, many diaspora Jews still embodied the Elephantine-type flexibility, explaining why his gospel could resonate with Jews and Gentiles who were devout but not fully Torah-bound.

Understanding this continuum—from Elephantine to Galatia—illuminates both the historical development of Judaism and the social context of Paul’s missionary work, highlighting how faith and law interacted in a changing world.

***

Jesus is Not Coming Down From the Sky

There is No Santa

Imagine a young boy who believes in Santa Claus. He believes that the presents he finds under the tree each Christmas morning were placed there by a magical man who came down the chimney, and who afterward hopped on his sleigh pulled by flying reindeer.

But, one Christmas Eve, the boy decides he wants to see Santa for real and so he sneaks out of his room late at night hoping to catch Santa in action. What he does see, however, is his own parents carefully laying out presents, one by one, around the base of the tree. And so, he knows the truth. It is in fact his own parents who are delivering the goods.

Now, with this knowledge, would it be proper for the boy to then believe that it is his own parents who slid down the chimney? And it his own parents who will fly off into the night on the sleigh? No, of course not. The boy must disregard the entire Santa narrative. There’s no one coming down the chimney. It’s all his parents buying the presents from the store, wrapping them out of sight, and placing them under the tree. Once the boy discovers the truth about one thing, he must apply that truth to everything else.

First Century Cosmology

First century Christians did not have telescopes. They believed the realm above them was a series of layers transcending the dome of the sky. They believed that angels and God literally resided in and above the layers containing the sun, moon, and stars. God’s throne room was a literal place up in what we would call “outer space.” When Jesus ascended up to the Father, to sit at His right hand, Jesus literally went up to sit on a literal throne in a literal throne room.

Since Jesus was up in outer space, of course when He returns, he will return from outer space. Where else would He come from?

21st Century Cosmology

Today we have telescopes. We know that we live in one galaxy among billions, and that each galaxy contains billions, if not trillions, of stars. The universe is so vast, it is beyond comprehension. In fact, the universe is likely infinite. We know this now.

We know that there is no Santa. Therefore, is it proper for us to continue to believe that one day the world will see Jesus descending down to the earth through the layers of the heavens as they believed He would in the 1st century? Should we combine their cosmology with our own? No, of course not. Ask any Christian today where heaven is, and unless he’s a flat-earther, he will likely say that heaven is located in the spiritual realm, someplace beyond the material realm that we do not have access to.

New Testament Eschatological Language

New Testament (NT) eschatology is primarily Israel’s eschatology. The Church’s eschatology builds upon it, but then transcends it. The cosmos coming under judgement for the NT authors was the Israelite cosmos. The end was near, at hand, at the door, soon, and about to happen. Every NT author believed he was living in the last days. And he was, to the degree that the old order of things was coming to an end. The apocalyptic language of the NT reflects this.

Israel’s eschatology is not the Church’s eschatology. The Church’s eschatology is this: Just as a dragnet draws all the fish into the boat, so is all creation being drawn to the Father by the redemptive work of Christ. We don’t know when this work will be complete, and we don’t know what it will finally look like. For now it is beyond our comprehension, beyond our reach.

It’s okay to be somewhat agnostic when it comes to eschatology. Embrace the mystery. Whatever you do, don’t go on believing that your dad has a pack of flying reindeer hidden away in a barn somewhere.

We Are Not Israel

Israel is gone. Our faith is not “Judeo/Christian.” We are just Christian. Yes, Jesus was the Messiah Israel was waiting for, but He was not the Messiah they were expecting. Jesus was not the blood soaked Davidic warrior coming to destroy Rome and establish a powerful Israelite theocracy the 1st century Jews were hoping for. This is why He was rejected.

Jesus subverted all Messianic expectations. His kingdom is not of this world. He came to conquer a higher enemy. He came to do the will of the Father, not Israel. The Father’s will is to redeem His creation. This is what Christianity is: The redemption of creation through Christ.

For Christians, Israel has become allegory. The Old Testament scriptures are transformed to types and shadows. It’s not our literal history. It’s our mythology.

Most Christians live like this even if not fully aware of it. They may say the stories are literal history, but they always apply the stories allegorically to their own life’s journey. It doesn’t matter if the stories are literal history or not; anything to do with Israel we allegorize.

Jesus is not coming down from the sky. Israelite cosmology is not true. That’s okay, because we are Christians. We know more. We’ve seen more. We know what is mythology and what is reality. We know the truth, and what we know is true; we must apply it to everything else.

David Bentley Hart and Eschatology

David Bentley Hart (an Eastern Orthodox scholar), in a series of articles concerning eschatology, writes: “[B]iblical eschatology is of its very nature … somewhat obscure on the actual details of how things end. Whatever it tells us—or hints at for us—comes in the often unintelligible form of elaborate symbolic fantasias and infuriatingly elliptical metaphors, all pronounced with an urgency soon belied by history’s perversely persistent failure to end. If we are to be strict and fastidious literalists about the language of scripture, the Lord, it would seem, has been coming “quickly” for two millennia now; the hour has been late since the days of the Caesars; the world that is passing away is doing so with all the hectic dispatch of molasses flowing uphill in February.”

Other than a shared expectation of a soon fulfillment of eschatological expectations, the New Testament authors give us no consolidated narrative. The traditional Christian eschatological storyline (Christ’s second coming, general resurrection, final judgment, eternal Kingdom) is not found in a unified form. Texts like Paul’s epistles, the Gospel of John, and Revelation offer distinct visions.

“My claims regarding the early Christian sense of a rapidly approaching ‘eschaton’ are, before all else, claims regarding the first epoch of the church as an association of believers in Christ who harbored a large variety of apocalyptic expectations, at once intrahistorical, truly eschatological, wholly eternal, or combining two or more of these in an indeterminate haze of anxious anticipation, fear, and hope. And I assume that it was only a sense of the imminent realization of those expectations that imposed any sort of uniformity on what was otherwise a farraginous collection of religious, political, cosmic, and psychological aspirations. The things that were coming soon from God—the things that lay just over the horizon of the present—were imagined in many forms and modalities, temporal and atemporal and both at once; but what was beyond doubt was that they absolutely must happen very soon (δεῖ γενέσθει ἐν τάχει, as the first verse of Revelation says), and this was the uniform confession and profoundly unified experience of believers.” (Hart)

Below is a summary of the various views of eschatology and resurrection the NT authors had, as presented by Hart in his articles…

1. Paul (Authentic Epistles: Romans, 1 & 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, Philemon)

- Eschatology: Paul’s eschatology is marked by an imminent expectation of Christ’s return (parousia) to consummate the present age and inaugurate the Kingdom (1 Thessalonians 4:13-17). He envisions a cosmic transformation where the “Age to Come” replaces the current order (1 Corinthians 15:24-28). Judgment is ambiguous, sometimes suggesting a selective process for the saved (Romans 8:11) and other times hinting at universal salvation (Romans 5:18; 1 Corinthians 15:28). Condemnation, if it occurs, consigns the reprobate to the past, not eternal torment (1 Corinthians 3:12-15). Paul’s focus is both intrahistorical (imminent divine intervention) and eternal (cosmic renewal).

- Resurrection: Resurrection is central to Paul’s theology, equated with salvation itself (1 Corinthians 15:42-50). It involves a transformation from a mortal “psychical body” (σῶμα ψυχικόν, animated by soul and flesh) to an imperishable “spiritual body” (σῶμα πνευματικόν), composed of spirit (πνεῦμα), akin to angelic or celestial beings. This transformation is conflated with an ascent through celestial spheres in Christ’s train at his return (1 Thessalonians 4:16-17; Philippians 3:20). Resurrection is primarily for the righteous, though universalist passages suggest broader inclusion (Romans 5:18).

- Key Features: Paul’s eschatology is future-oriented but imminent, with a strong universalist undercurrent. Resurrection is a cosmic, spiritual event, reflecting first-century cosmology where spirit is a subtle, incorruptible element.

2. Synoptic Gospels (Mark, Matthew, Luke)

- Eschatology: The Synoptics blend intrahistorical and eternal horizons, with a strong preterist emphasis on first-century events, particularly the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE (Olivet Discourse: Mark 13; Matthew 24; Luke 21). Jesus’ prophecies use prophetic idioms (e.g., Isaiah 65:17-25) to depict historical calamities as cosmic upheavals, targeting the rich and powerful for their oppression (Matthew 25:31-46). Judgment is often intrahistorical (e.g., within a generation, Matthew 24:34), but a secondary eschatological horizon of divine justice looms (Matthew 11:22-24:11). The Kingdom is both imminent (Luke 11:20) and present within believers (Luke 17:20-21), with varied fates for the unrighteous (e.g., destruction, exclusion, temporary chastisement). Matthew’s allegory of judgment (Matthew 25:31-46) is a gathering of nations, not a resurrection event. Mark mentions resurrection only once (Mark 12:25), and Luke links it to the righteous (Luke 14:14).

- Resurrection: In the dispute with the Sadducees (Mark 12:25; Matthew 22:30; Luke 20:35-36), Jesus describes the resurrected as “like angels” or “equal to angels” (ἰσάγγελοι), implying a spiritual, eternal existence free from marriage and death. Resurrection is not clearly tied to judgment, and its nature remains ambiguous. Luke’s depiction of the risen Christ with “flesh and bones” (Luke 24:39) contrasts with this angelic vision, suggesting potential inconsistency or redaction. Mark’s minimal focus on resurrection may align with spiritual ascent or soul revival.

- Key Features: The Synoptics’ eschatology is heavily preterist, with metaphorical language tied to historical events. Resurrection is symbolic and ambiguous, often reserved for the righteous, with a focus on ethical transformation.

3. Gospel of John

- Eschatology: John’s eschatology is predominantly realized, emphasizing the present reality of eternal life through faith in Christ (John 5:24; 11:25). The Kingdom is marginalized, replaced by “eternal life” (aiōnios zōē), which collapses future expectations into the now. Judgment is immediate, occurring in Christ’s crucifixion, which casts out the world’s Archon and draws all to himself (John 12:31-32). While a future resurrection and judgment are mentioned (John 5:28-29), these are qualified as already present (John 5:25: “the hour is coming”). The “last day” is the cross, where history and eternity meet (John 12:48). John’s universalist tone suggests all are redeemed through Christ’s act (John 12:32).

- Resurrection: Resurrection is both a future event (John 5:28-29) and a present reality (John 11:25: “I am the resurrection and the life”). Believers already possess eternal life through faith, transcending death (John 6:47; 8:51). Resurrection is an ascent to a supercelestial reality, described as aiōnios, likely indicating a divine, eternal realm akin to Plato’s Timaeus. John lacks a final ascension scene, portraying Christ as continually present (John 20:19-28).

- Key Features: John’s eschatology is radically present-focused, with judgment and resurrection fulfilled in Christ’s life, death, and resurrection. The universalist vision reconciles historical and eternal horizons.

4. 1 Peter

- Eschatology: 1 Peter has a future-oriented eschatology, anticipating Christ’s return and final judgment (1 Peter 4:7). However, it also hints at a realized dimension, with Christ’s resurrection enabling spiritual actions (e.g., preaching to the “spirits in prison,” 1 Peter 3:18-19). Judgment is linked to historical suffering and divine vindication, but not explicitly tied to a universal resurrection.

- Resurrection: Christ’s resurrection is described as a transformation from flesh to spirit (1 Peter 3:18: “put to death in flesh, made alive in spirit”), enabling him to enter spiritual realms. This aligns with Paul’s spiritual body concept, suggesting a non-carnal, angelic existence for the resurrected.

- Key Features: 1 Peter bridges future and realized eschatology, with resurrection as a spiritual transformation, reinforcing the apostolic view of an imperishable state.

5. Hebrews

- Eschatology: Hebrews shifts from imminent historical expectations to a vertical, transcendent eschatology. Christ’s second coming is mentioned (Hebrews 9:28), but the focus is on his present role as High Priest in the heavenly sanctuary (Hebrews 4:14; 8:1). Salvation is an ascent to the “world above,” emphasizing a timeless divine reality over future consummation.

- Resurrection: Resurrection is implicit in the ascent to the heavenly places, where believers are drawn by Christ’s priestly work (Hebrews 6:19-20). It is not detailed but aligns with a spiritual, non-carnal transformation.

- Key Features: Hebrews prioritizes a vertical eschatology, with resurrection as a spiritual ascent, reflecting a shift from historical to eternal concerns.

6. Pseudo-Pauline Texts (Ephesians, Colossians, 2 Thessalonians, 2 Timothy)

- Eschatology: These texts reflect responses to delayed expectations. Ephesians and Colossians emphasize a realized eschatology, with believers already “raised” and “seated” with Christ in heavenly places (Ephesians 2:6; Colossians 3:1-2), though future consummation is noted (Ephesians 1:10). 2 Thessalonians, likely non-Pauline, introduces an intermediate period of apostasy and the “man of lawlessness” to explain Christ’s delay (2 Thessalonians 2:1-3), insisting on future divine intervention. 2 Timothy refutes claims of a mystical resurrection, maintaining future imminence (2 Timothy 2:17-18).

- Resurrection: Ephesians and Colossians view resurrection as a present spiritual reality, aligning with John’s eternal life. 2 Thessalonians and 2 Timothy anticipate a future bodily resurrection, possibly for both just and unjust (Acts 24:15, though not pseudo-Pauline).

- Key Features: These texts show a transition from Paul’s imminent eschatology to realized or adjusted expectations, with resurrection varying from present to future.

7. Revelation

- Eschatology: Revelation is primarily preterist, focusing on the fall of Rome and the establishment of a new Jerusalem (Revelation 21:1-5). It adopts apocalyptic imagery, including a millennial messianic reign and two resurrections (Revelation 20:4-6), but these inaugurate a new epoch, not history’s end. Judgment is symbolic, tied to political and spiritual aspirations rather than a final cosmic assize.

- Resurrection: The first resurrection is for martyrs during the millennial reign, the second a universal judgment (Revelation 20:11-15). Both are symbolic, reflecting anti-Roman hopes rather than literal eschatology.

- Key Features: Revelation’s eschatology is allegorical and preterist, with resurrections as political symbols, not doctrinal statements.

Differences in New Testament Eschatology and Resurrection

| Author/Text | Eschatology (Kingdom, Judgment) | Resurrection | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paul (Authentic) | Imminent parousia, cosmic transformation (1 Thess 4:13-17). Judgment ambiguous, possibly universal (Rom 5:18). Kingdom is future “Age to Come” (1 Cor 15:24-28). | Spiritual transformation into imperishable “spiritual body” (1 Cor 15:42-50), conflated with celestial ascent (1 Thess 4:16-17). Primarily for righteous. | Future-oriented, universalist hints, spiritual resurrection, first-century cosmology. |

| Synoptics (Mark, Matthew, Luke) | Preterist focus on AD 70 (Olivet Discourse: Mk 13; Mt 24; Lk 21). Judgment intrahistorical (Mt 25:31-46) with eternal horizon. Kingdom imminent and present (Lk 17:20-21). | Angelic, non-carnal existence (Mk 12:25; Lk 20:35-36). Vague, possibly for righteous only (Lk 14:14). Luke’s “flesh and bones” (Lk 24:39) inconsistent. | Metaphorical, preterist, ethical focus, ambiguous resurrection. |

| John | Realized eschatology: eternal life now (Jn 5:24; 11:25). Judgment immediate, on cross (Jn 12:31-32). Kingdom marginalized, universalist tone. | Present eternal life through faith (Jn 11:25), also future (Jn 5:28-29). Ascent to supercelestial reality, no final ascension scene (Jn 20:19-28). | Radically present, universalist, eternal life as aiōnios reality. |

| 1 Peter | Future-oriented, with Christ’s return and judgment (1 Pet 4:7). Some realized elements (1 Pet 3:18-19). | Christ’s resurrection as shift to spirit (1 Pet 3:18), enabling spiritual realms. Aligns with Paul’s spiritual body. | Bridges future and realized, spiritual resurrection. |

| Hebrews | Vertical, transcendent eschatology. Christ as High Priest in heaven (Heb 4:14). Future coming secondary (Heb 9:28). | Implicit as spiritual ascent to heavenly places (Heb 6:19-20), non-carnal. | Vertical focus, present salvation, minimal resurrection detail. |

| Pseudo-Pauline (Eph, Col, 2 Thess, 2 Tim) | Mixed: realized in Eph/Col (Eph 2:6), future with delays in 2 Thess (2:1-3), 2 Tim (2:17-18). Judgment varies. | Present spiritual raising (Eph 2:6; Col 3:1-2) or future bodily (2 Thess, 2 Tim, cf. Acts 24:15). | Transition from imminent to realized or adjusted, varied resurrection views. |

| Revelation | Preterist, anti-Roman focus (Rev 21:1-5). Millennial reign, symbolic judgments (Rev 20:11-15). New epoch, not history’s end. | Two symbolic resurrections: martyrs’ reign, universal judgment (Rev 20:4-6). Political, not doctrinal. | Allegorical, preterist, symbolic resurrections, political critique. |