And only by this primordial assent does humanity in its eternal “multi-hypostatic” reality— as the eternal Adam of the first creation— freely receive its being from its creator: and this even though that assent becomes, on the threshold between the heavenly Aeon and time, a recapitulation of the Fall, an individuating acceptance of entry into the world under the burden of sin, such that every soul is answerable for and somehow always remembers that original transgression. In that moment, the spiritual creature concurs in its own creation, and God hands the creature over to its own free self-determination. Here, naturally, the language of past and future can devolve all too easily into a mythology of individual guilt historically “prior” to any person’s actual life; but, of course, there was no fall “back then” in historical time, either for the race or for the individual. Rather, the Fall “happened” only as belonging to the temporal unfolding of that eternal assent. It “happened”— or, rather, is happening— only as the lingering resistance of nothingness to that final joyous confession, the diminishing residue of the creature’s emergence ex nihilo. For no creature can exist as spirit in God except under the condition of having arisen from nothingness in order to grow into his or her last end. That passage from nothingness into the infinite, which is always a free intentionality toward a final cause, is the very structure of created spiritual beings. They could not be spirit otherwise.

David Bentley Hart, You Are Gods (Kindle Locations 2269-2281). University of Notre Dame Press. Kindle Edition.

The above quote is dense. I had ChatGPT break it down for me…

1. Humanity’s “primordial assent”

- All of humanity, seen as one great reality (called here the “eternal Adam”), says “yes” to God in a timeless, original way — that’s what allows us to receive our existence.

- This assent is not something we’re forced into; it’s freely given.

2. Entry into the world as a re-enactment of the Fall

- When each soul crosses from God’s eternal realm into time, that assent gets played out again.

- This entry into earthly life also means accepting a world where sin and brokenness exist — a “burden” every soul bears.

- Somehow, each person participates in and “remembers” the original turning away from God (the Fall), even though it’s not a literal memory of a past historical event.

3. Individual freedom at creation

- In this moment of entering existence, the soul agrees to be created and is entrusted by God to its own freedom.

- God hands each creature over to its own self-determination — we’re not puppets; we live by our own will.

4. The caution against misreading the Fall

- It’s easy to turn this idea into a story of “individual guilt” for something that happened before we were born.

- But the author says that’s a misunderstanding — the Fall wasn’t a single event in history, for either humanity as a whole or for each person individually.

5. The Fall as an ongoing reality

- The Fall “happens” as part of the unfolding of that original assent in time.

- It’s the ongoing resistance of nothingness — the fact that we came from nothing — to fully and joyfully uniting with God.

- This resistance gradually diminishes as we grow toward God.

6. Why this resistance exists

- A creature can only exist as a spiritual being in God if it has come from nothingness.

- That means we must grow from nothingness toward our ultimate purpose — union with God — in a free, intentional way.

- That journey from nothing to infinite life in God is the very structure of what it means to be a spiritual creature.

In short:

We each freely agree to exist, but entering the world means stepping into a condition where sin already burdens us — not as guilt for a past event, but as part of our starting point in nothingness. The Fall is not “back then,” but is the ongoing process of wrestling with the pull of nothingness as we freely move toward God, which is exactly what it means to be a spiritual being.

***

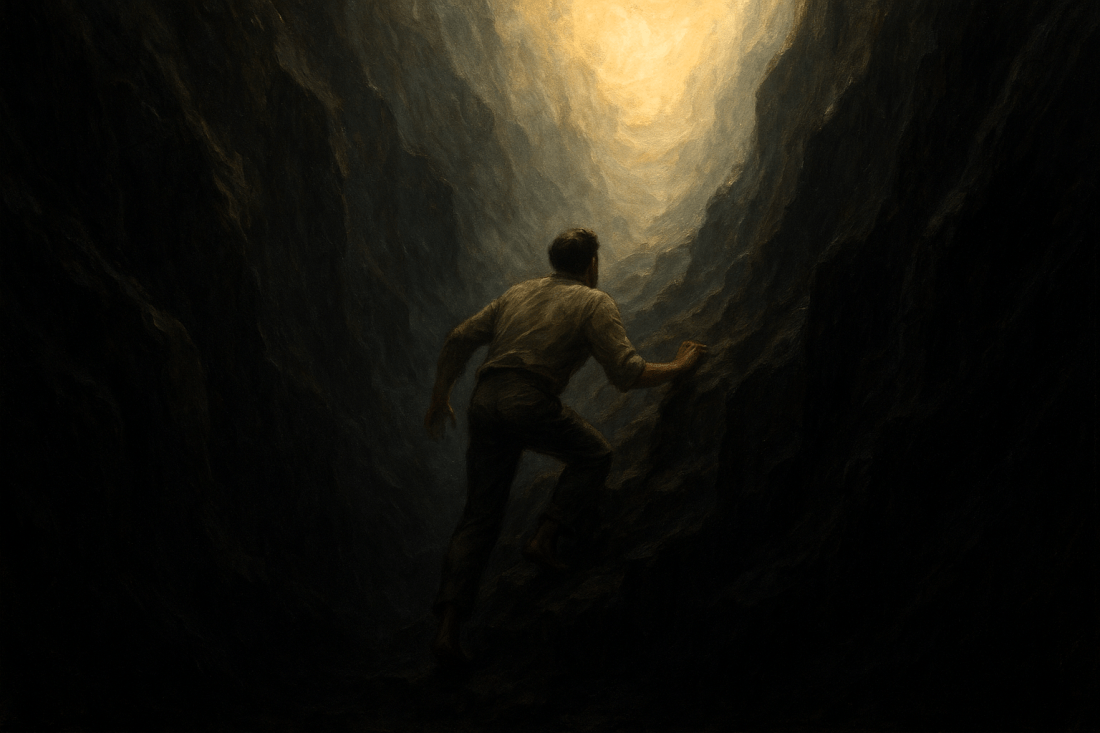

The Climb from the Hollow

In the beginning, there was no beginning.

Ermias opened his eyes in a vast, dim hollow. No sun, no stars; only a faint glow far above, like the hint of a dawn. He did not remember falling here; he simply found himself at the bottom, his feet in the dust.

He stood. Something inside him whispered: Up there is your home.

Not a command, but an invitation.

The climb was hard. The walls were steep in some places, treacherous in others, and the dust clung to him, weighing him down. It whispered, You come from me. Stay. It pulled at his ankles, reminding him how easy it would be to stop.

Ermias kept climbing.

Not because he was told to, not because he feared punishment, but because the faint light above called to him. The higher he climbed, the stronger the light, and the lighter his steps.

Still, the dust never let go. Even when he could see the edge of the hollow, its pull was there, a quiet ache in his legs and longing in his chest. It was part of him, just as much as the light.

He understood:

He had not been pushed into the hollow long ago. He had always been here, and his life was the climb — the slow, free, deliberate rising from the nothingness of the dust toward the fullness of the light.

***

If we view the fall in this way, how does the life of Jesus guide us from nothingness to God?

- Complete Surrender to God’s Purpose and Freedom from Nothingness:

- Jesus embodies complete surrender to God’s purpose, demonstrating the free intentionality required to move from nothingness toward divine union. His prayer in Gethsemane, “Not my will, but yours be done” (Luke 22:42), illustrates this active, free choice to embrace his divine end.

- Unlike every other human being, Jesus’ freedom was never bent inward toward self-assertion. Every choice He made aligned perfectly with the will of the Father, overcoming the pull of nothingness.

- Incarnation as the Bridge from Nothingness to Infinity:

- The doctrine of the Incarnation (God becoming human in Jesus – John 1:14) illustrates the journey from nothingness to divine fullness. As fully human, Jesus shares in the creaturely condition of originating ex nihilo, yet as fully divine, he embodies the infinite end toward which all creatures are called.

- Jesus entered the same condition we inhabit—born into the finitude and vulnerability of human life, subject to temptation, pain, and mortality. By living our condition without turning inward, He shows that the journey from nothingness to God can be completed within human limits.

- Overcoming Temptation as Resistance to Nothingness:

- The temptation of Jesus in the wilderness (Matthew 4:1-11, Luke 4:1-13) symbolizes the rejection of the “residue of nothingness.” Satan’s temptations—material gain, power, and self-preservation—represent ways the creature might cling to autonomy or finite desires, resisting divine intentionality. Jesus’ refusal of these temptations demonstrates how to prioritize God’s will over the allure of nothingness.

- His temptations in the wilderness are the archetypal moment where the pull of “nothingness” tries to assert itself—through comfort, power, and self-display. Jesus answers each one with trust in the Father, refusing the shortcuts that would anchor Him in self-will.

- Teachings as a Guide for Intentionality:

- Jesus’ teachings in the Gospels, such as the Sermon on the Mount (Matthew 5-7), outline a way of life that orients the soul toward God. His emphasis on love, humility, forgiveness, and trust in God offers a roadmap for aligning one’s intentions with divine purpose.

- Jesus describes His very sustenance as obedience to God’s purpose—“My food is to do the will of Him who sent me, and to finish His work” (John 4:34), showcasing the opposite of clinging to self-sufficiency.

- Crucifixion as the Ultimate Surrender:

- Jesus’ death on the cross (Mark 15:33-39, John 19:30) represents the ultimate act of self-emptying (kenosis), where he freely embraces the finitude and suffering inherent in creaturely existence. By accepting death, Jesus confronts the nothingness at the heart of human mortality and transforms it through his trust in God’s redemptive power.

- On the cross, Jesus fully experiences the consequence of our condition: mortality, weakness, and even the feeling of God’s absence. But instead of yielding to despair, He entrusts Himself entirely into the Father’s hands, reversing the “Fall” by freely surrendering to Him in suffering.

- Resurrection as the Fulfillment of Divine End:

- The resurrection (Matthew 28:1-10, John 20:1-18) is the definitive triumph over nothingness, demonstrating that the journey from ex nihilo to God culminates in eternal life. Jesus’ risen life shows that the creature’s free assent to God’s purpose leads to transformation beyond the limits of finitude.

- The resurrection is not just a miracle to prove divinity—it’s the completion of the passage from nothingness into the infinite. In Him, human life is lifted fully into God, body and soul, showing the destiny that awaits every spirit that freely assents.

- Example for Practical Imitation:

- Jesus’ life provides concrete practices for moving toward God: prayer (e.g., the Lord’s Prayer, Matthew 6:9-13), service to others (John 13:1-17), and sacrificial love (John 15:13). These actions reflect a life oriented toward divine intentionality, showing how everyday choices can resist nothingness and grow toward God.

- Jesus’ whole life shows what it looks like when created spirit fully grows into its “last end”—unbroken union with God, serving as the pattern and pioneer of what it means for created spirit to complete the climb from the Hollow to the Summit.

A question often asked about the Adam and Eve story is: Why did they fall? And why so quickly? If all was perfect and wonderful, why did they fall at all?

A question often asked about the Adam and Eve story is: Why did they fall? And why so quickly? If all was perfect and wonderful, why did they fall at all?